Literary Manuscripts

Literary manuscripts include a wide variety of text and can be divided into, for example, saga manuscripts and manuscripts preserving texts written in verse.

Saga manuscripts

The term 'saga manuscripts' refers to the manuscripts that entirely or mostly contain sagas, i.e. medieval stories in prose in Old Norse (Norwegian or Icelandic) on important people's life and family. Saga literature consists of various different saga genres, which are presented in the column to the right.

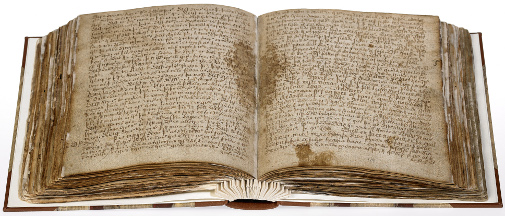

Rask 32. Saga manuscript from the end of the 18th century

Rask 32 is a manuscript from the end of the 18th century that contains a compilation of fornaldarsögur and riddarasögur in Icelandic. Its unremarkable appearance and the heavily worn state tell us that it has been used and read by many (whose names we find today in numerous marginalia). There is a table of contents at the back of the first leaf.

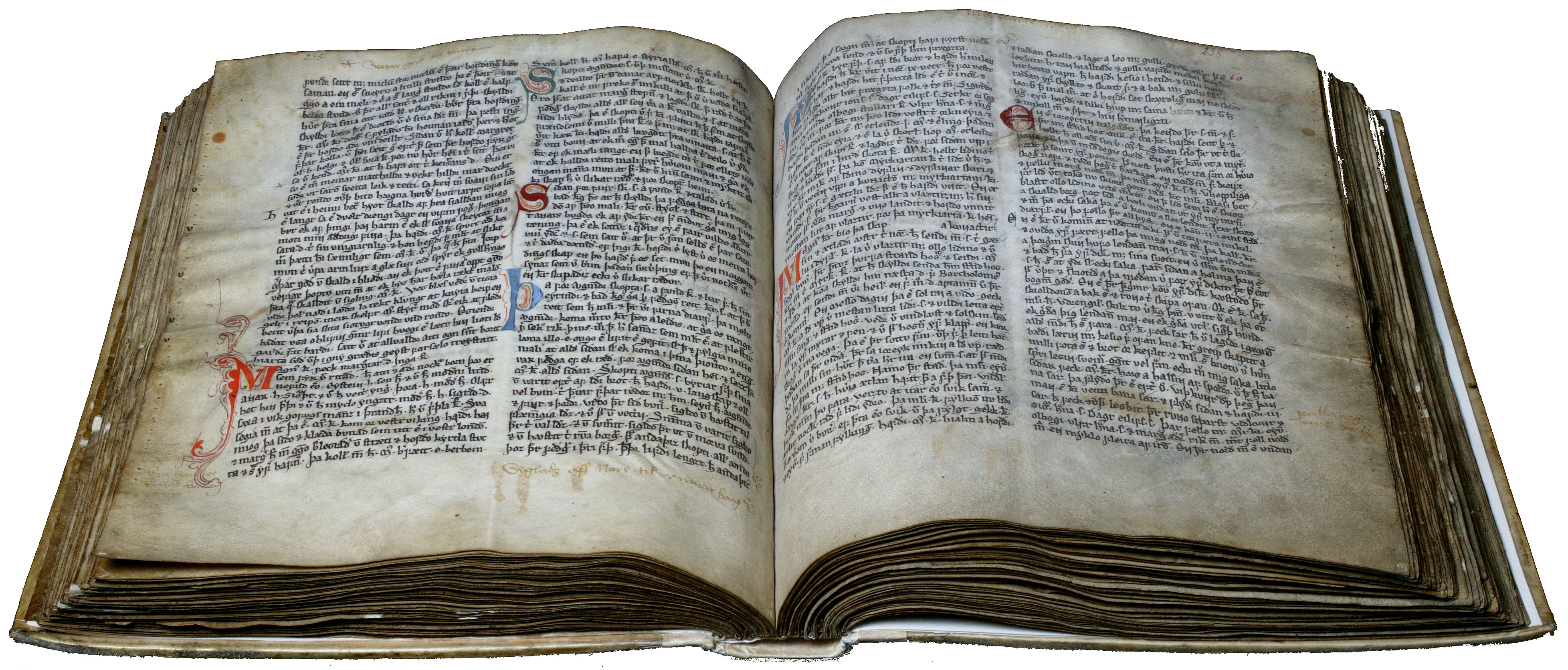

AM 45 fol. Codex Frisianus: Norwegian kings' sagas

AM 45 fol. is a manuscript from the first quarter of the 14th century that contains Heimskringla (the circle of the world), i.e. the Norwegian kings' sagas from mythical times until 1177, and the saga of Hákon Hákonarson. The name 'Codex Frisianus' stems from the fact that the first known owner of the manuscript was the Danish nobleman Otto Friis.

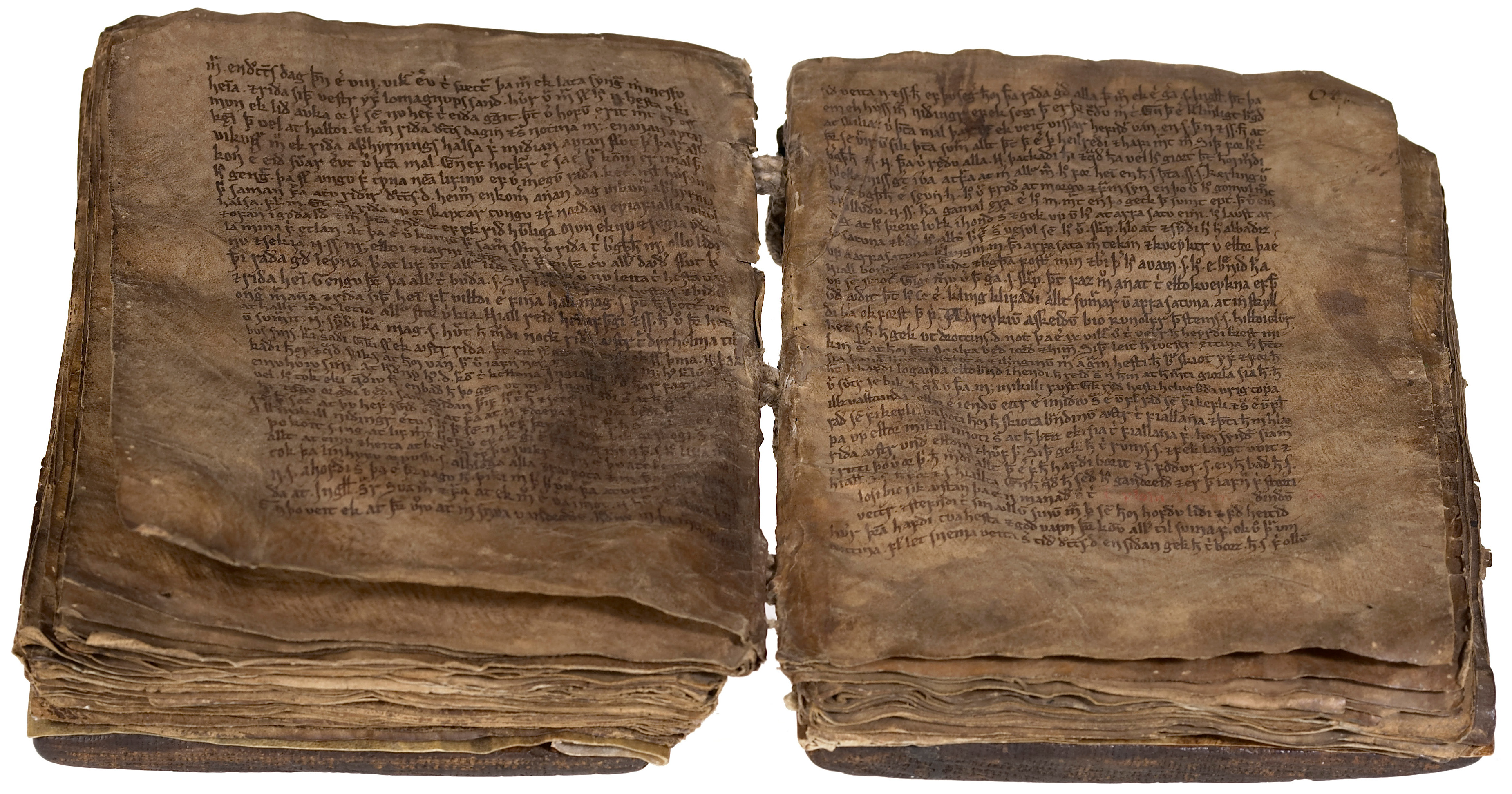

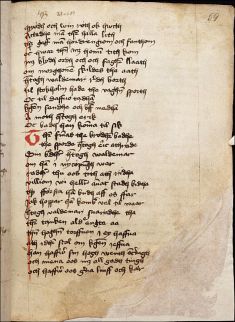

AM 468 4to. Reykjabók: Njál's saga

AM 468 4to is a manuscript from around 1300. It contains nearly the entire text of Njál's saga, a saga of Icelanders. It got its nickname from its first known owner's place of residence at the beginning of the 1600s: the farm Reykir in Miðfjörður. Despite its modest appearance, it is one of the most important manuscripts preserved from the Middle Ages, partly because it contains Njál's saga, and partly because of its age: its date of writing is close to the first writing down of the saga. Click on the picture to turn the pages in the manuscript.

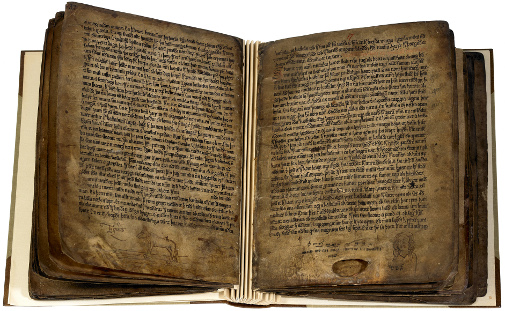

AM 595 a-b 4to. The saga of the Romans

AM 595 a-b 4to from 1325-1350 contains the so-called Rómverja saga, the saga of the Romans. The saga is an edited compilation of three Icelandic translations of three Latin works from the 1st century: Bellum Jugurthinum and Catilinae coniuratio by the Roman historian Sallust and Pharsalia by the Roman poet Lucan. Only 38 out of the original 76 leaves are preserved. The manuscript, which probably originates from the monastery Þingeyrar in the Northwestern part of Iceland, is remarkable because of its numerous marginalia that sometimes relates directly to the text, and other times are later additions without any connection to the text: drawings, prayers, proverbs, verses or single words. There are contemporary drawings on several pages. See pictures of these drawings in the margins in AM 595 a-b 4to on the page on marginalia.

Literature written in verse

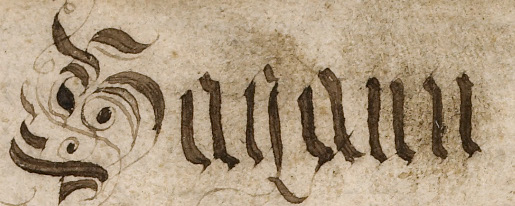

Beginning of the Swedish chivalric romance Flores och Blanzeflor from 1312: As I in books read and as the legend narrates...

Literature written in verse arrived in the North with the translation of continental courtly literature in the 12th century. The term 'literature written in verse' includes several types of literature: the courtly literature, translated from French or German originals, which consists of love stories with the courtly ideal as its moralising background; the historical chronicles, a genre that started in France in the 12th century, which uses verses to narrate kings' feats with emphasis on their courtly qualities; and the ballads, i.e. sung or danced short stories of knights shaped after the French troubadours' oral story-telling, which became popular in Denmark in the 13th century. They were rediscovered in the 17th century, during which time most of them were written down.

AM 191 fol.: Codex Askabyensis

AM 191 fol., or Codex Askabyensis, from the end of the 15th century, contains various texts written in verse. It contains among others the chivalric romance of Flores and Blancheflor in Swedish, a translation of the French Floire et Blancheflor, and Den lille Rimkrønike.

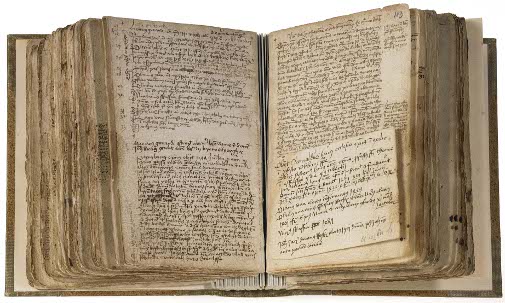

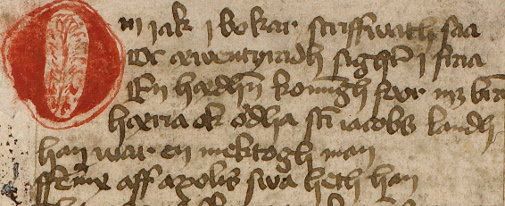

AM 107 8vo: the Danish Rhymed Chronicle

AM 107 8vo is a manuscript from the 16th century that contains the entire Rhymed Chronicle. The Chronicle lets the kings themselves, from Dan's father Humble up to Christian I, narrate their feats in verses.

Literary Manuscripts Monthly

Fornaldarsögur

The Arnamagnæan Institute in Copenhagen is conducting a research project on the origins and transmission of the Icelandic fornaldarsögur. Read more about the project here.

Types of sagas

Sagas of Icelanders: Approximately 40 sagas of Icelanders (íslendingasögur) have been handed down to us. Before they were written down by unknown authors, they had been transmitted orally from generation to generation. The events usually take place around the time of the settlement of Iceland (landnám) until the time when Christianity arrived in Iceland. They can either tell the story of a single hero (Gunnlaugs saga ormstungu) or of a whole family (Gísla saga Súrssonar).

Kings' sagas: The sagas of kings (konungasögur) may either have been written in Iceland or Norway. The first one was written around 1100. The most famous collection of these is probably the one found in Heimskringla which contains among others the saga of St. Olaf.

Chivalric sagas: or the sagas of knights (riddarasögur) are translated works, usually from the French chansons de geste, that tell stories of courtly knights. These are the most important in quantity among the literature we know from Norway in the 13th century.

Legendary sagas: The fornaldarsögur were primarily written for entertainment purposes. They tell stories of heroes in Scandinavia, usually with supernatural powers, from before the settlement of Iceland.

þættir: These are short stories which in the genre may resemble all the other types of sagas. As opposed to the Icelandic sagas where the heroes are from rather wealthy families, the heroes in the þættir may belong to any social class and not possess the skills that would usually define an ideal Nordic male.

The Danish Rhymed Chronicle

Read about the Danish Rhymed Chronicle on smn.dsl.dk or read the whole text in normalised edition.

Erikskrönikan

Read about Erikskrönikan on Fornsvenska Textbanken.