Courtly Love under the Bishop's Mitre

How did leaves from a 13th-century Norwegian manuscript containing 12th-century French profane tales of fervent love end up as the stiffening for a 16th-century Icelandic bishop’s mitre?

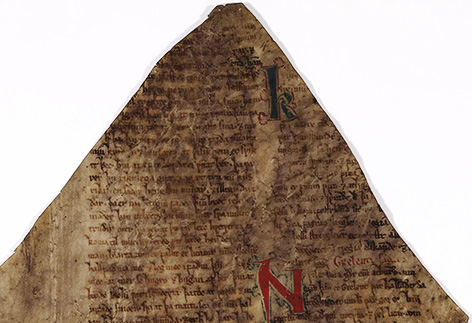

One of the stories the bishop had unwittingly been carrying around on his head tells of a knight, Grelent, and his fascination for a woman who was more beautiful than the queen of the country. (Click to see a larger version)

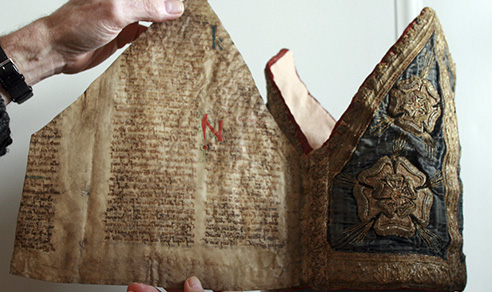

At one point during his stay in Iceland from 1702 to 1712 Árni Magnússon found at the episcopal see of Skálholt a bishop’s mitre from Catholic times. One can easily imagine his surprise when he found that under the rotten silken lining the inner reinforcement of the mitre was made of old manuscript leaves, and he must surely have been amused when he realised that the text on these leaves consisted of profane tales of fervent love. There were four leaves, two bifolia, from a beautiful parchment manuscript written in two columns. They had been cut in the same triangular shape and size and sewn together to make the skeleton for the mitre. The language of the text shows that the manuscript was written in the southwest of Norway around 1270.

The reuse of manuscripts

But how did four leaves from a Norwegian manuscript end up as the stiffening for an Icelandic bishop’s mitre? Until the Reformation, Iceland was under the archiepiscopal see of Nidaros (Trondheim), and so any newly elected bishop had to travel there to receive his insignia. It has thus been suggested that this mitre was sewn to measure in Nidaros, probably around the year 1500, but it has not been possible to identify the specific bishop for whom this was done. If the mitre is held against the light, the sewing holes from borders and rosettes become visible, making it almost possible to reconstruct the embroidered decorations. In the National Museum in Copenhagen there is another bishop’s mitre from Skálholt from the beginning of the sixteenth century, from which it is possible to get an idea of what it may have looked like. This mitre was sold at an auction in 1802 of the inventory of the bishop’s see, which had been abolished in 1797. It was bought by Skúli Thorlacius (1741–1815), who in 1813 gave it to Den kgl. Oldsagskommission (The Royal Antiquities Commission).

Far-travelled stories

Although one might assume that the rest of the manuscript from which these leaves were taken has been lost, as so often happened with such fragments, this is not the case here. The manuscript to which these four leaves belonged is kept today at the University Library in Uppsala, where it has the shelfmark DG 4–7 fol. The Danish historian and editor of Saxo, Stephan Stephanius, got the manuscript from Norway in around 1630, had it bound and added a table of contents in Latin. A couple of years after his death in 1650, his manuscript collection was bought by the Swedish nobleman Magnus Gabriel de la Gardie, who in turn donated it to Uppsala University Library in 1669. Out of the original 56 leaves, a quarter appear to have been lost; of the last quire, which was used for the bishop’s mitre, only two leaves remain.

DG 4–7 fol. is one of the oldest and most important Norwegian manuscripts containing courtly literature. The longest text in the book is the so-called Strengleikar, translations of 21 Old French courtly love poems into Old Norse prose. Most of them are attributed to Marie de France (twelfth century). One of the stories the bishop had unwittingly been carrying around on his head tells of a knight, Grelent, and his fascination for a woman who was more beautiful than the queen of the country. The Strengleikar, which are only found in this manuscript, were like other representatives of European courtly literature translated at the initiative of King Håkon Håkonsson, Håkon the Old (1204–1263).

- Peter Springborg

In the National Museum in Copenhagen there is another bishop’s mitre from Skálholt from the beginning of the sixteenth century, from which it is possible to get an idea of what the other one may have looked like.