Pointing out Manicules in AM 76 8vo

Marginal annotations are a popular way to interact with a text; AM 76 8vo showcases manicules, a form of marginalia that literally gets the point across.

A Danish manuscript from the late 15th century, AM 76 8vo contains fifty-eight different texts, mostly consisting of liturgies, hymns, and charms. It also contains the only surviving manuscript copy in Old Danish of Lucidarius, an anonymous medieval work that detailed religious beliefs and, later, general knowledge. The fact that the manuscript contains many different works is typical for those composed and copied throughout the Middle Ages. (There’s so much going on in this manuscript that this is even the second time it’s been nominated as Manuscript of the Month; for an overview of the manuscript, you can read Britta Olrik Frederiksen’s post: “A School Teacher’s Handbook.”)

While paleographical evidence reveals that multiple scribes worked on the manuscript, it is difficult to determine where precisely one scribal hand ends and another begins (see A Danish Teacher's Manual Vol.2). Some of the sections have more cramped writing and others more free flowing, often while using similar letterforms; it is therefore challenging to say whether this is evidence of a new scribe at work or the same scribe working more hurriedly (or simply having switched to a new pen nib).

Alongside the text appear the marginal annotations, a mix of inscriptions performed both by the scribes and by the later readers. Scribes of the main texts were not always responsible for marginal decorations and annotations, as there were many people involved in a manuscript’s production and transmission. For instance, rubricators were responsible for writing the bits of the text that required red ink, and illuminators were responsible for drawing decorated initials or gilding parts of the manuscripts. Later, readers would interact, often physically, with the manuscript, leaving traces of themselves through marginal doodles or short scribbled notes. The textual history of the manuscript doesn’t end when a scribe finishes the last word of the main text, but continues throughout the reader responses and interactions with the entire manuscript. In the course of this manuscript, there are multiple marginal annotations and images, including notes (f.18r), crosses (f. 18v), flowers (f. 16r), and pen flourishes (f. 62r). There are also manicules.

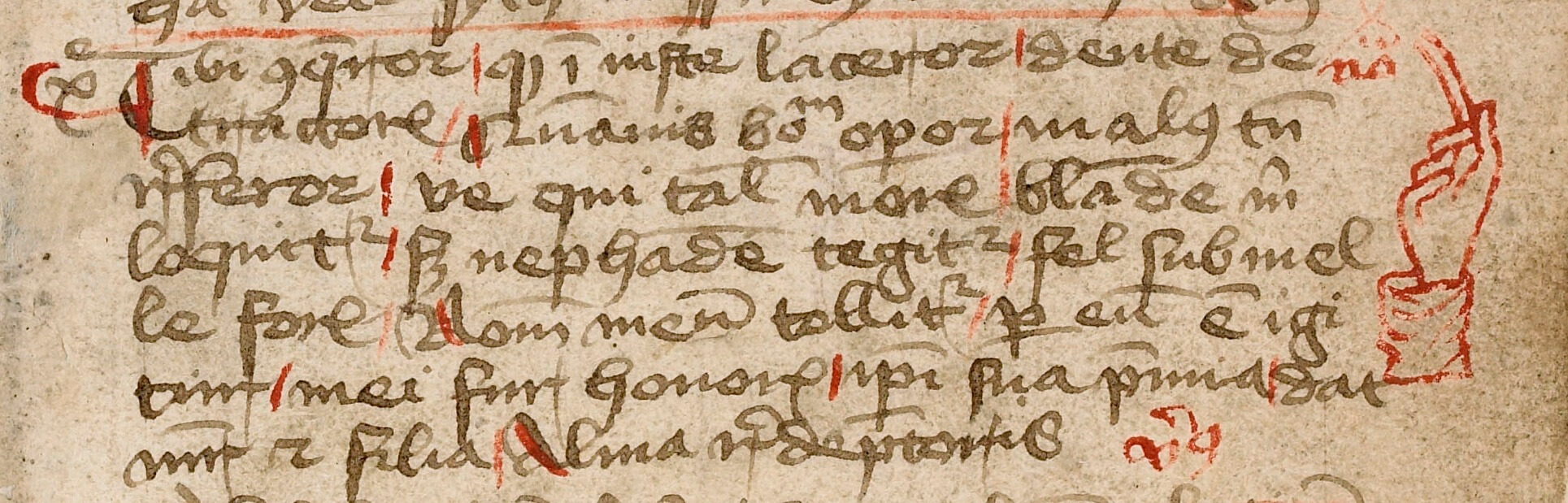

A hand in red points to the opening of the alphabetical prayer to the Virgin Mary (AM 76 8vo, f. 11r. Photo: Suzanne Reitz. Click for full image.)

As a form of marginalia, manicules are straightforward to identify because they are always shaped like hands. From the Latin word manicula, meaning “little hand,” manicules can be detailed in their depictions, with intricate sleeve cuffs or anatomically correct fingernails; they can also be simple sketches that only give the impression of a hand and additional fingers. These hands always have extended index fingers (sometimes comically so) that mark significant passages. Why those particular spots are chosen can vary wildly based on who drew the manicules; some examples include emendations or additions, particularly noteworthy passages, or perhaps even favorite bits of text.

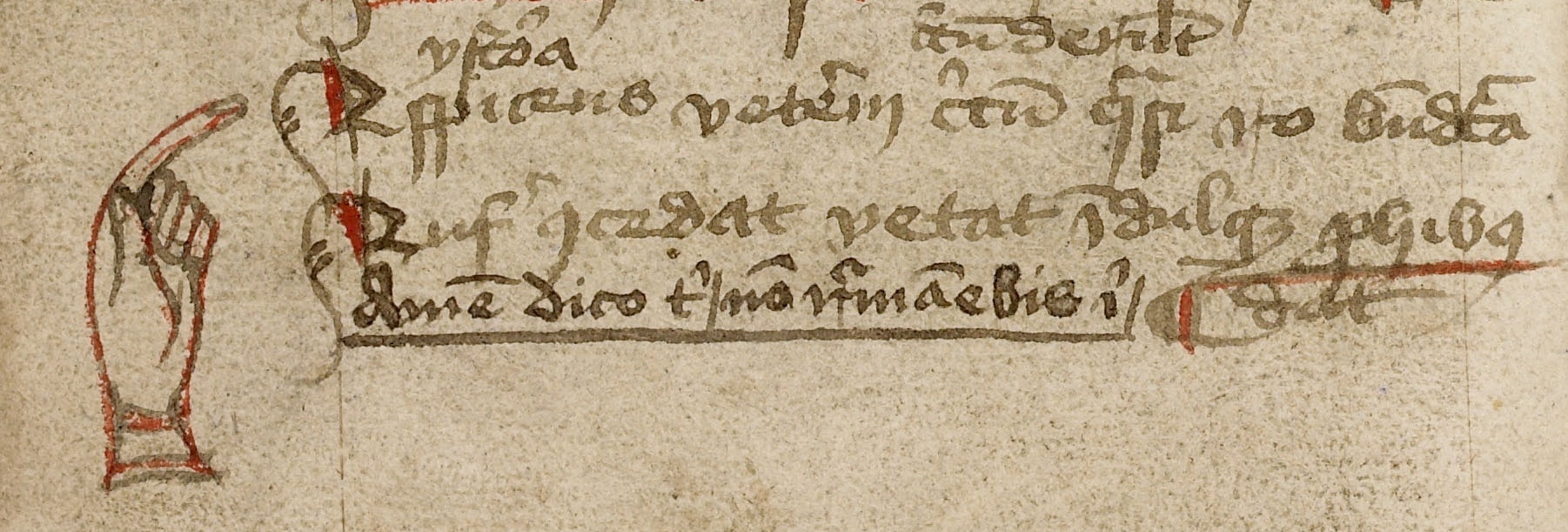

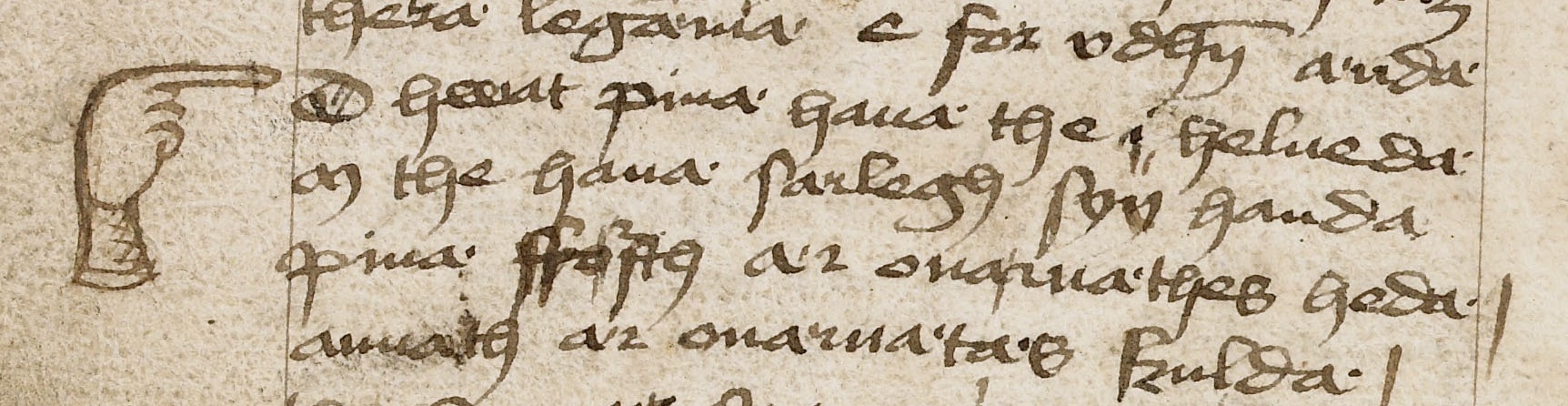

A left-handed manicule points to the section on mnemonics (AM 76 8vo, f. 20v. Photo: Suzanne Reitz. Click for full image.)

Six manicules, drawn by two different people, appear in the margins in the course of the manuscript. The first three manicules appear on folios 9r, 11r, and 20v. When viewed together, a pattern forms: All three of these are the openings of new works. The first manicule (f. 9r), in red ink, points between lines 11 and 12, where a poem in praise of the Virgin Mary ends and a poem about jealousy and drinking begins. The second manicule (f. 11r), again inked in red, points to the opening of an alphabetical prayer to the Virgin Mary on line 17. The text that precedes this actually ends on the previous page, but the alphabetical prayer is first ascribed to Pope Urban V, with indulgence; the manicule clears any potential confusion by pointing to the formal opening of the alphabetical prayer. The third manicule (f. 20v), inked in both red and black, points to line 20 where a short section on mnemonics begins. In all of these, where the visual difference isn’t stark between the closing of one section and the opening of another, the manicules clarify the organization of the text.

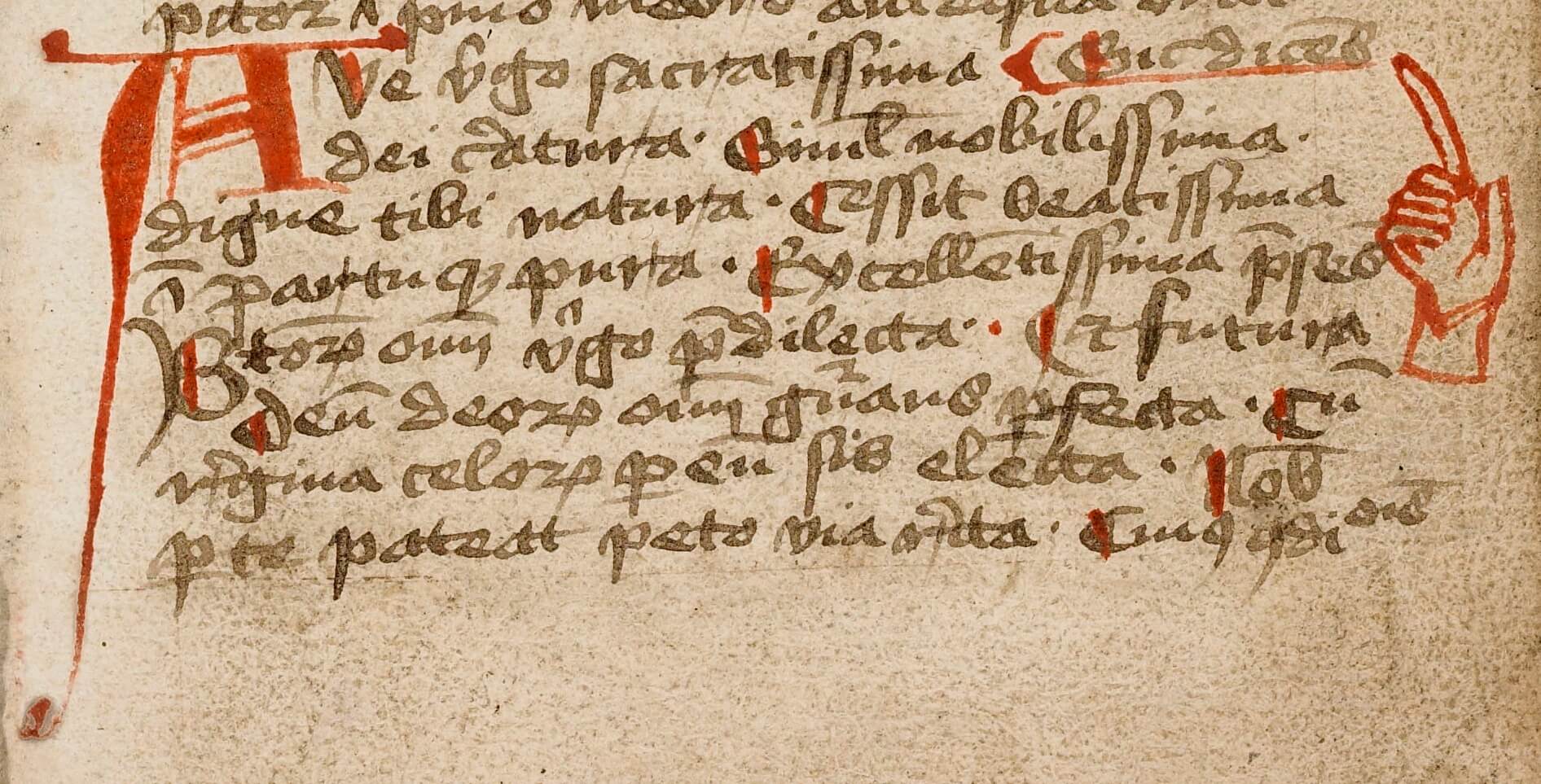

A hand with a cross-hatched sleeve points to the text of Lucidarius. (AM 76 8vo, f. 60r. Photo: Suzanne Reitz. Click for full image.)

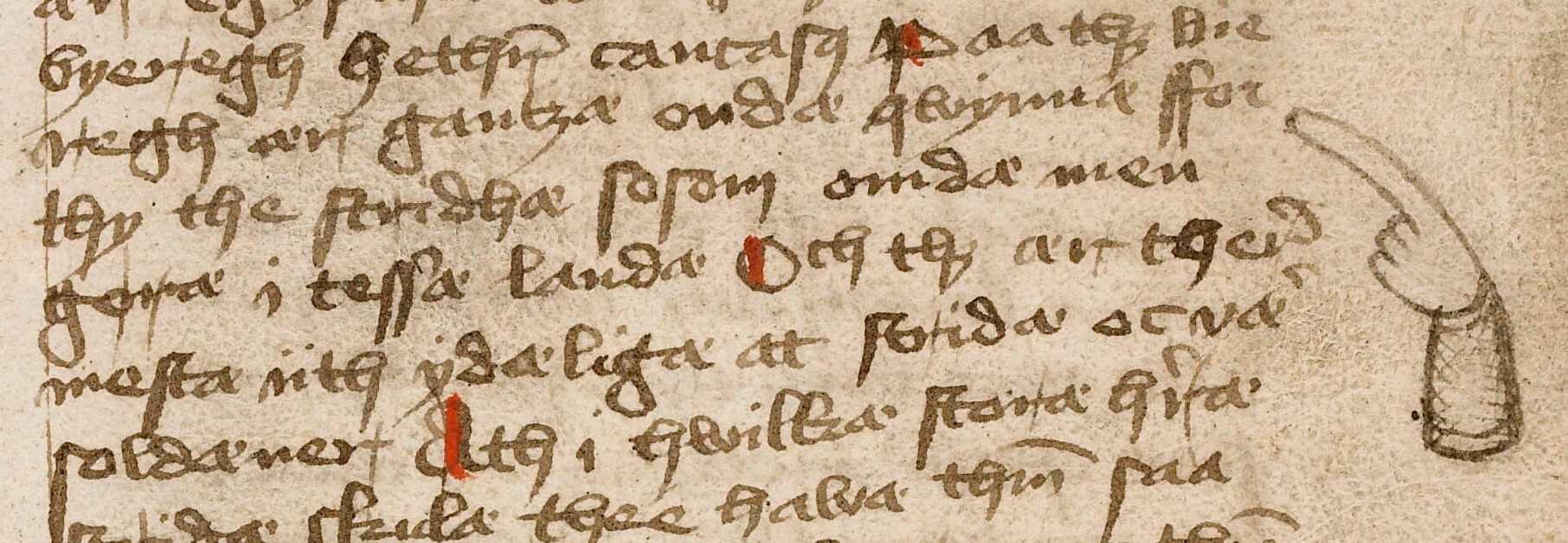

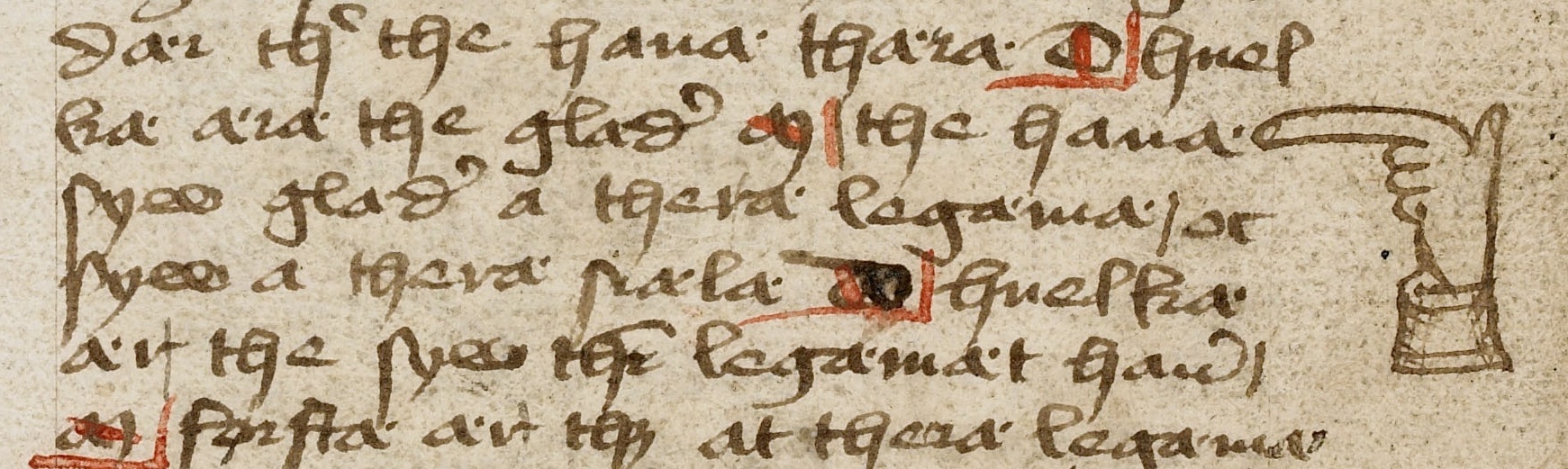

While all those manicules appear in the first quarter of the manuscript, we don’t come across the next manicule until we reach the middle half of the manuscript. There, in the span of 12 pages (a similar spread to the first set), we see three manicules, all gesturing towards passages in Lucidarius. The manicules (ff. 60r, 66v, 72r) are now all drawn with black iron gall, not red ink, and exhibit cross-hatched shading on their sleeve cuffs. Two of them have fingernails. All of these manicules direct the reader’s attention to noteworthy passages, as determined by the person who drew them.

A right hand in the left margin points to the text of Lucidarius. (AM 76 8vo, f. 66v. Photo: Suzanne Reitz. Click for full image.)

Just like the first set of manicules, the second set is closely grouped together. However, unlike the first set of manicules, the second set is not drawn by a scribe or rubricator to provide organizational clarity but is instead likely drawn by a reader as a way to demarcate passages of interest. The artistic styles also indicate a similarity between manicules in each set. (Look more closely – the manicules on folios 11r and 20v, for instance, both have six fingers.) What we have here are two different inscribers, with two different motives.

A right hand appears to give a thumbs up while pointing to the text of Lucidarius. (AM 76 8vo, 72r. Photo: Suzanne Reitz. Click for full image.)

Alongside flowers, asterisks, and writing out the word nota (‘note’), manicules are one of the primary forms of marginalia throughout the manuscript period. Even after the proliferation of printed books, manicules were seen as an essential element of engagement with the text. Printers and typesetters offered manicules as typographical marks to assist publishers in directing readers’ attention. (As there was no standardization of the term, these were offered under various names such as “pointing hands” or “mutton fists.”) Even now, manicules persist in advertisements and signage, if not in books themselves.

☞ Let’s have a show of hands for the humble manicule! ☜

Topics

Contact

Arendse Lund is a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellow at the Arnamagnæan Institute, University of Copenhagen.

Bibliography

Anne Mette Hansen, “Manicula,” Encyclopædica Britannica: Festskrift til Britta Olrik Frederiksen i anledning af hendes 60-årsdag sen 5. december 2007. Grammel, F., Louis-Jensen, J. & Mósesdóttir, R. (eds.)., København: Museum Tusculanum (2007), 87-92

Marius Kristensen, En Klosterbog fra Middelalderens Slutning (AM. 76, 8vo.), J. Jørgensen & Co., 1933.

Britta Olrik Frederiksen, et al. (ed.): A Danish Teacher's Manual of the Mid-Fifteenth Century (Cod. AM 76, 8⁰). Vol. 2, Commentary and Essays, Vetenskapssocieteten in Lund, Skrifter, 96, 2008.

Sigurd Kroon, et al. (ed.): A Danish Teacher's Manual of the Mid-Fifteenth Century (Cod. AM 76, 8⁰), Lund 1993.

William H. Sherman, Used Books: Marking Readers in Renaissance England, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010.

Funding

This entry of Manuscript of the Month was produced in connection the LAWS project, which has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 126637

Contribute to Manuscript of the Month

Have something to say about one or more manuscripts in the Arnamagnæn Collection? Contribute to the column Manuscript of the Month to get your research out there! Write to Seán Vrieland (sean.vrieland@hum.ku.dk) for more details.