Priceless manuscripts on loan to Iceland

Yesterday two manuscripts from the Arnamagnæan Manuscript Collection were flown to Iceland, where they will be on display in the exhibition Lífsblómið - Fullveldi Íslands í 100 ár (Blossoming - Iceland’s 100 Years as a Sovereign State) at the National Gallery of Iceland in collaboration with Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies.

The manuscripts in question, AM 242 fol. (Codex Wormianus), containing the Prose Edda, and AM 468 4to (Reykjabók), containing the oldest almost complete copy of Njáls saga, were escorted by the police from Keflavík Airport to the University of Iceland, where they were presented to the assembled press.The Arnamagnæan Collection has close ties to its sister-institute in Reykjavík, and we are very pleased to be able to participate in the celebrations in connection with the centenary of Icelandic sovereignty by sharing two of the most important Icelandic medieval manuscripts.

Reykjabók was written in Iceland around 1300, and while it may not be among the most visually impressive manuscripts, it is very much a question of not judging a book by its cover. The manuscript is one of the main manuscripts of Njáls saga, one of the most famous of the Icelandic Sagas, containing the oldest almost complete text of the story (a single leaf is missing). It is a well-travelled manuscript, which came to Copenhagen for the first time in the 1640s, before being moved to The Netherlands, where it was owned by the Dutch orientalist Jakob Golius (1596–1657). It remained in The Netherlands until it was bought by Danish book-collector Niels Foss (1670–1751) in 1696 and was taken back to Copenhagen. Árni Magnússon bought the manuscript from Foss in 1707 and had it sent to Iceland, where his brother made an exact copy. In 1722 it returned to Copenhagen, and now it has made its fourth journey across the Atlantic.

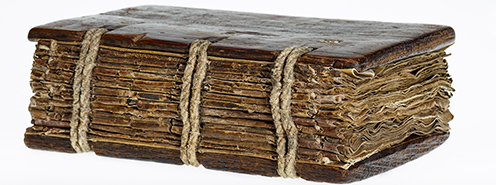

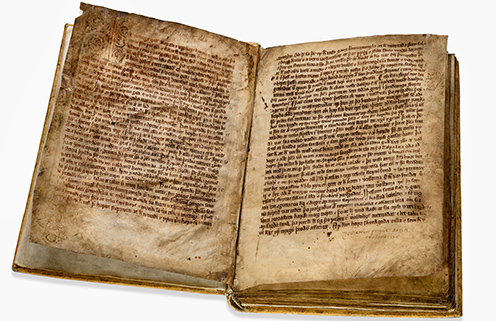

Codex Wormianus (The Book of Worm) gets its nickname from its previous owner, Danish physician and antiquarian Ole Worm (1588-1654). It is dated to the mid-14th century and contains Snorri’s Edda and the four grammatical treatises on the Icelandic language. The first page of the manuscript states that it was given to Ole Worm by Arngrímur Jónsson (Olai Wormii – dono Arngrimi Jonæ Islandi), one of the key figures of the Icelandic Renaissance. Former head of the Arnamagnæan Institute Peter Springborg has called this gift “emblematic for Danish-Icelandic research cooperation throughout the ages”.

When Ole Worm received the manuscript he had the pages washed in urine in order to lighten them to make them more legible, and while our conservators have not had to go through that again, they have been busy preparing the manuscripts for their trip to Iceland. Both manuscripts are in good condition, so they have not needed much restoration, but because they are to be exhibited, our conservators have had to make sure that they aren’t damaged from being held open for a longer period of time. For instance, conservator Natasha Fazlić has measured the optimal angle at which the books should be opened so as not to damage the spines, and these measurements have been sent to Iceland where book supports have been made to measure.

Our photographer, Suzanne Reitz, has taken new portraits of both manuscripts, and they have both previously been digitised so scholars can continue to work with them while they are on loan. The new portraits of Reykjabók will also be featured in the exhibition Hånden og Ordet (The Hand and the Word) at Nordatlantens Brygge, and a replica of Reykjabók is also being made for exhibition in Copenhagen this autumn. The conservators and photographer have therefore been comparing colour samples to the original manuscript to make sure that the replica is as authentic-looking as possible.

Even if you’ll not be in Reykjavík or Copenhagen this year, you can still admire Codex Wormianus and Reykjabók, as they are both available on handrit.org.

Contact

Anne Mette Hansen is an associate professor and curator of the Arnamagnæan Manuscript Collection.

E-mail: amh@hum.ku.dk