Inside the binding of AM 779 c 4to

A manuscript containing copies of Claus Lyschander's The Greenland Chronicle in two different Icelandic translations rather surprisingly also contains a small text fragment of a dialogue between two women on the duties of wives. How and why has this come about, and who might have been responsible for the binding?

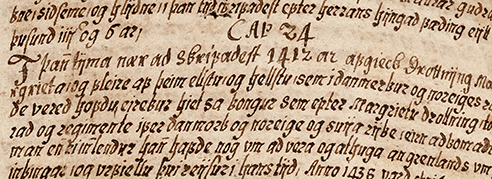

Árni Magnússon's own handwritten notes about the contents of the manuscript. (Click on the picture to see a larger version.)

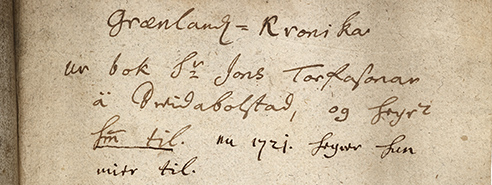

AM 779 c 4to is a seventeenth-century paper manuscript that mostly contains rhymed chronicles about Greenland. More specifically, it holds five handwritten copies of Claus Lyschander’s (1558-1623/24) The Greenland Chronicle in two different Icelandic translations. (The Danish original Den Grønlandske Chronica was published in 1608.) In addition, the manuscript contains a small text fragment of completely different nature and otherwise unknown contents.

A stowaway?

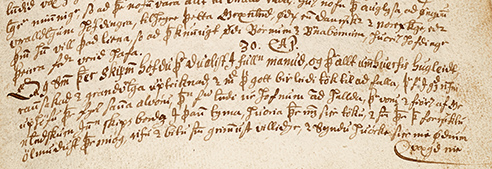

There is an inscription on the spine detailing the contents of the manuscript. (Click on the picture to see a larger version.)

The manuscript’s 130 leaves are bound in a half binding. The boards on both front and back are covered with marbled paper, and the corners and spine show greenish-blue binding tape. On the spine it has golden imprints: Horizontal lines imitating raised bands divide the surface of the spine into five fields, and in the second field from the top, the following title is engraved: „Varia Exscripta Chronici Grönlandici cum tïtulis manu A. MAGNÄI adscriptis“ (Various copies of the Greenland Chronicles with titles added in the hand of A. Magnæus [=Árni Magnússon]). This inscription hints at the main contents of the manuscript, the five chronicle copies. It does not mention a sixth text, though, which is located inside the same binding: Following the first copy of the Greenland chronicle, there are four somewhat smaller leaves carrying a fragment of a dialogue between two women on the duties of wives. The names of the characters are abbreviated as “A:” and “B:” which is interpreted as Agatha and Barbara, (possibly Saint Agatha and Saint Barbara) in Kålund’s catalogue (1889-1894, II, p. 200). The text is in Icelandic and its textual origins have not been investigated yet. This seems to be its only preserved copy in an Icelandic manuscript, however, which makes one wonder even more how it came to be in the same manuscript as the Greenland chronicles.

Annotated by Árni Magnússon himself

The five copies of the Greenland chronicle have associated note slips, on which Árni left some brief provenance information. In all but the first slip, he also identified the work, as is noted in the golden spine inscription. According to these note slips, Árni received the copies from five different origins in Iceland. The fragment, on the other hand, does not carry any note, which is why nothing is known about its provenance. The only hint at its history is the fact that the four leaves are written by the same unidentified hand as the first chronicle copy. It is thus possible that the two parts came to Árni together, in which case they would have the same provenance. Since the note slip found with that first copy does not identify the text or texts it applies to, it could indeed apply to both. However, as Árni left no note or explicit remark about the four additional leaves, it cannot be ruled out that the fragment was combined with the larger leaves based on the common scribe at a later point.

When and by whom was the manuscript bound?

The current binding of AM 779 c 4to was given to the manuscript some time between 1730 and 1894. In other words it was produced after Árni Magnússon’s death. This information can be derived, among others, from the characteristic gilded decoration of its spine. In addition to the mentioned title and horizontal lines, the spine shows a crowned national arms of Denmark in its lowest field. The coat of arms contains three lions and is supported by two savages with bludgeons. Hanging below it is the Order of the Elephant, an order associated with the Danish royal family. Accordingly, this binding can be linked to the Royal Library in Copenhagen, where the manuscript was kept for some time. It was then registered as NkS 1961 4to and placed with the royal manuscripts instead of being with the rest of the Arnamagnæan manuscripts in the University library. In April 1888 it was finally returned to its place among Árni’s manuscripts (see Kålund 1900, p. 263).

Since the current binding is from after Árni Magnússon’s death, the manuscript could have had slightly different contents during his lifetime. In fact, when the whole collection was first catalogued after Árni’s death in 1730, the manuscript was registered as containing two additional copies of the Greenland chronicle. (The copies in question are today called AM 779 a and b 4to.) The fragment about Agatha and Barbara is not mentioned there. That could potentially mean it was not contained by the larger manuscript yet. On the other hand, it is also conceivable that the fragment’s text had been forgotten during the cataloguing. This could easily have happened, since the script is the same as on the previous leaves and there is neither a clear rubric on the fragment nor a visually prominent end on the last leaf of the first chronicle copy, its end also being defective. When quickly flipping through, the two parts may have thus been mistaken as forming a single text. At the very least, it can be assumed that this is what happened when the manuscript was given its current binding, explaining why the engraved title is silent about the additional text.

Contact

Beeke Stegmann is a postdoctoral researcher at the Arnamagnæan Institute.

Tlf. +45 3533 5746

beeke.stegmann@hum.ku.dk

Beeke wrote her PhD thesis on Árni Mangússon's rearrangement of paper manuscripts. It is a codicological study of 17th and early 18th-century codices that were taken apart and rearranged by Árni Magnússon. Read more on the project website.