Getting a fair share: an Icelandic letter of partition from 1673

Two small fragments found in the binding of an Icelandic manuscript tell the story of how a farmer divided the inheritance between his two sons.

The classic fairy tale Puss in Boots begins with a miller on his deathbed, dividing his possessions between his three sons. The miller makes a blatantly unfair division of property: the eldest gets the mill, the middle son gets the donkey, and the youngest gets the cat.

Fortunately, the cat has a cunning plan.

It was to prevent this sort of situation from occurring in real life that inheritance laws requiring written documentation of a deceased person’s estate and the fair division of property between children were developed in the Nordic countries. In the kingdom of Denmark-Norway, a series of laws and decrees were passed during the seventeenth century that called for official documentation and assessment of estates. Maintenance of written records was particularly emphasised in cases where minor children were among the heirs.

Families in the seventeenth century were often complex, with children from multiple marriages entitled to a share in the estate. By the end of the century, it was fairly standard practice in Denmark and Norway to make an extremely detailed written inventory of a deceased man’s possessions if he was survived by underage children. These records protected the interests of minors, not least in the event of disputes between family members over how to divide an estate between the legal heirs.

Not much evidence survives of administrative practices surrounding estates and the division of inheritance in Iceland during the same period. Icelandic historian Már Jónsson has written extensively on the subject of probate records in Iceland and other parts of Scandinavia. In contrast to an abundance of material from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Már has identified only a handful of surviving probate records for Iceland in 1651–1700, the oldest being for a wealthy bishop of Iceland, Þorlákur Skúlason, who died in 1656.

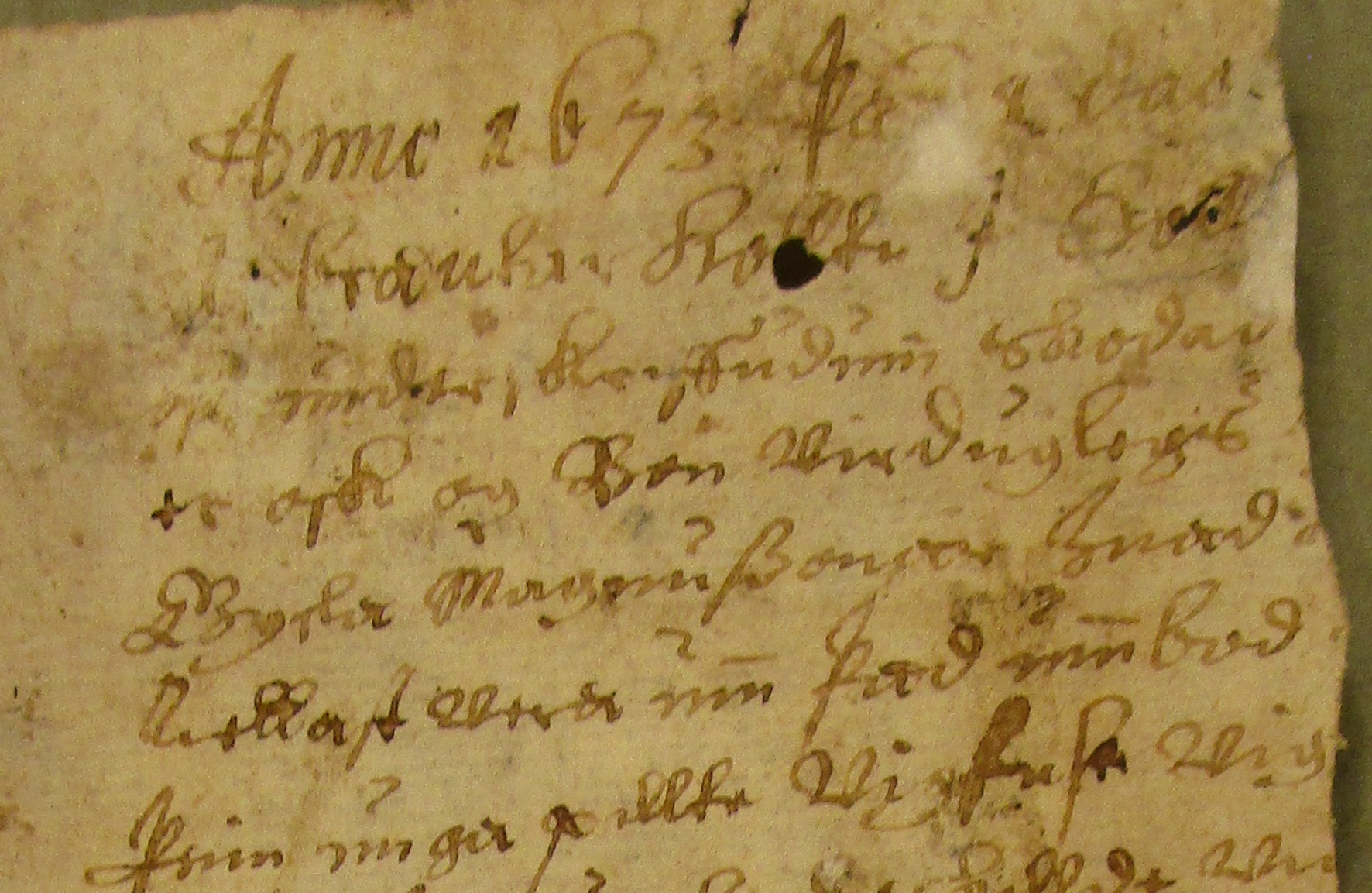

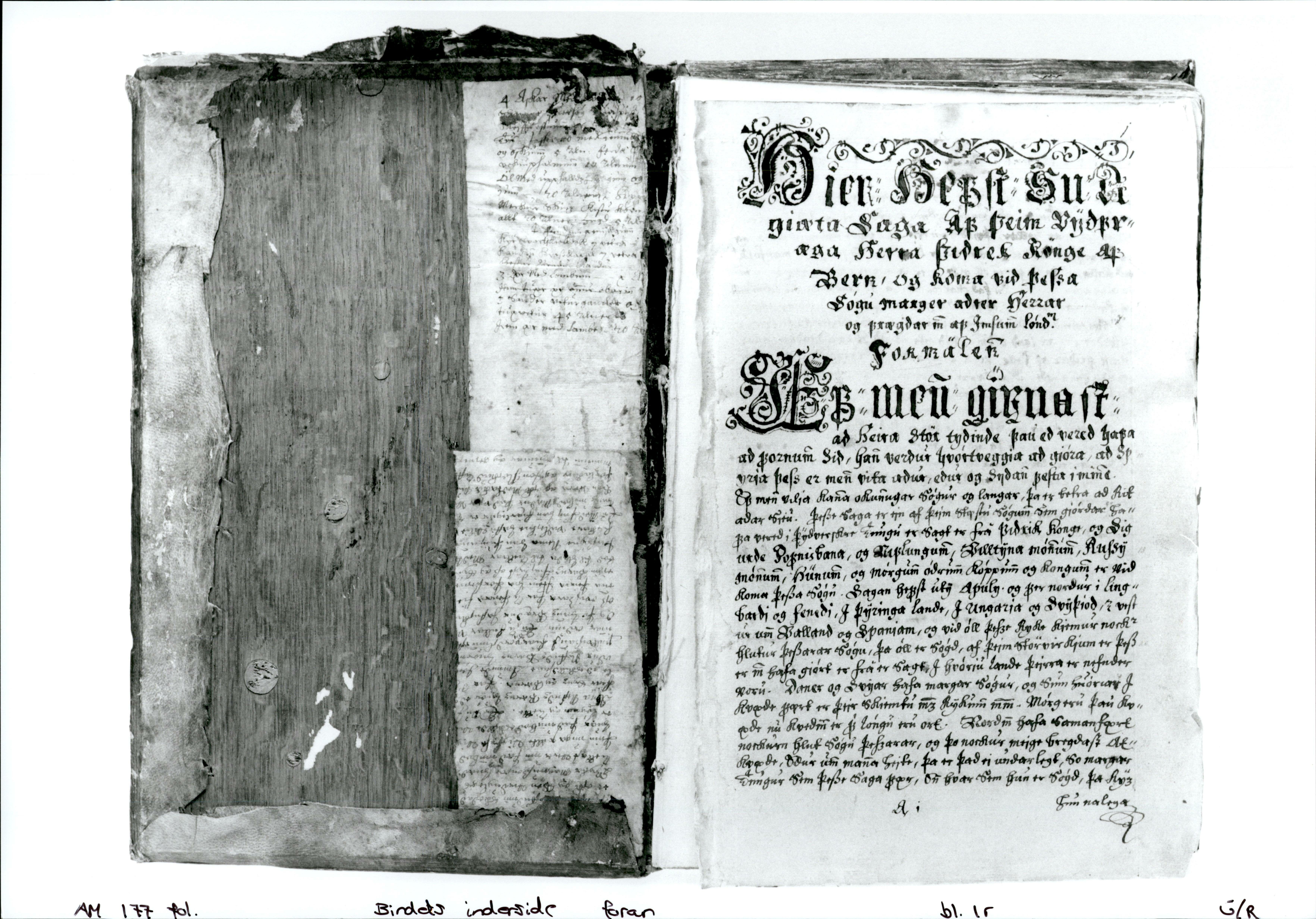

Fortunately, old probate records make excellent scrap paper. Two fragments of a so-called letter of partition surfaced in the binding of AM 177 fol. during its restoration at the Arnamagnæan Institute in Copenhagen, led by conservator Natasha Fazlic. They relate to the estate of Vigfús Ólafsson of Akbrautarholt in South Iceland, who died in 1673.

Vigfús Ólafsson was an ordinary tenant farmer. No other documents survive on Vigfús’s birth, life or death. From what remains of the letter of partition, we can see that he had at least two sons. The elder son’s name is Ólafur, presumably named after Vigfús’s father. Vigfús also had a son whose name was Vigfús and was still a child at the time of his father’s death.

A census of the entire Icelandic population took place in 1703, at which time an Ólafur Vigfússon (b. about 1655) farmed at the nearby tenancy of Lækur in the commune of Holtamannahreppur. He was married and had an 18-year-old son from an earlier marriage or relationship. There is only one man named Vigfús Vigfússon in the 1707 census of the correct age to be Vigfús Ólafsson’s son. He was 39 years old farmed at Vindás in the commune of Landmannahreppur, which is also in the district of Rangárvallasýsla in South Iceland. Vigfús was married and had two very young children. A 63-year-old woman who is probably Vigfús’s mother, Þórunn Vigfúsdóttir, was living with the family at Vindás. This Vigfús was a successful farmer who lived at least to 1729.

If the Ólafur Vigfússon and Vigfús Vigfússon in the 1703 census are identical with those named in the document, then they would have been around 25 and 9 respectively when their father died. In this case, Þórunn was plainly not Ólafur’s mother, as she was only eight years older than the farmer at Lækur. While it is impossible to absolutely certain that these men were the sons of Vigfús Ólafsson of Akbrautarholt, a complex family situation such as this is the most plausible scenario in which this type of a detailed letter of partition on the Danish model was drawn up.

The fragmentary state of the documents in the binding in AM 177 fol. does not allow a complete reconstruction of the farm household at Akbrautarholt in 1673. We can see, however, that they owned livestock (including a cow with black spots), farming equipment and at least one printed book. On one fragment, containing the list of Ólafur’s share in his father’s estate, seems to have had additions and corrections inserted, suggesting that this list was drawn up at Akbrautarholt as the valuation and division of property was taking place and was a document in progress.

The two fragments from Akbrautarholt represent the oldest surviving Icelandic probate record for an Icelandic peasant. They provide a tiny window into the near-invisible lives of ordinary people in early modern Iceland.

Contact

Katelin Parsons is a Ph.D. student at the University of Iceland and guest researcher at the Arnamagnæan Institute.

Katelin Parsons is a Ph.D. student at the University of Iceland and guest researcher at the Arnamagnæan Institute.

Bibliography

Már Jónsson, “Securing inheritance: Probate processeding in the Nordic countries, 1600–1800,” Sjuttonhundratal 13 (2016): 7-30.

Már Jónsson, “Skiptabækur og dánarbú 1740–1900: Lagalegar forsendur og varðveisla,” Saga 50.1 (2012): 78–103.