Behold! A Funen Clog!

Humorous marginal drawings are not uncommon in medieval manuscripts. The wooden shoe from Funen found in the margin of AM 23 8vo, however, is more than just for laughs: it is a commentary on the surrounding legal text.

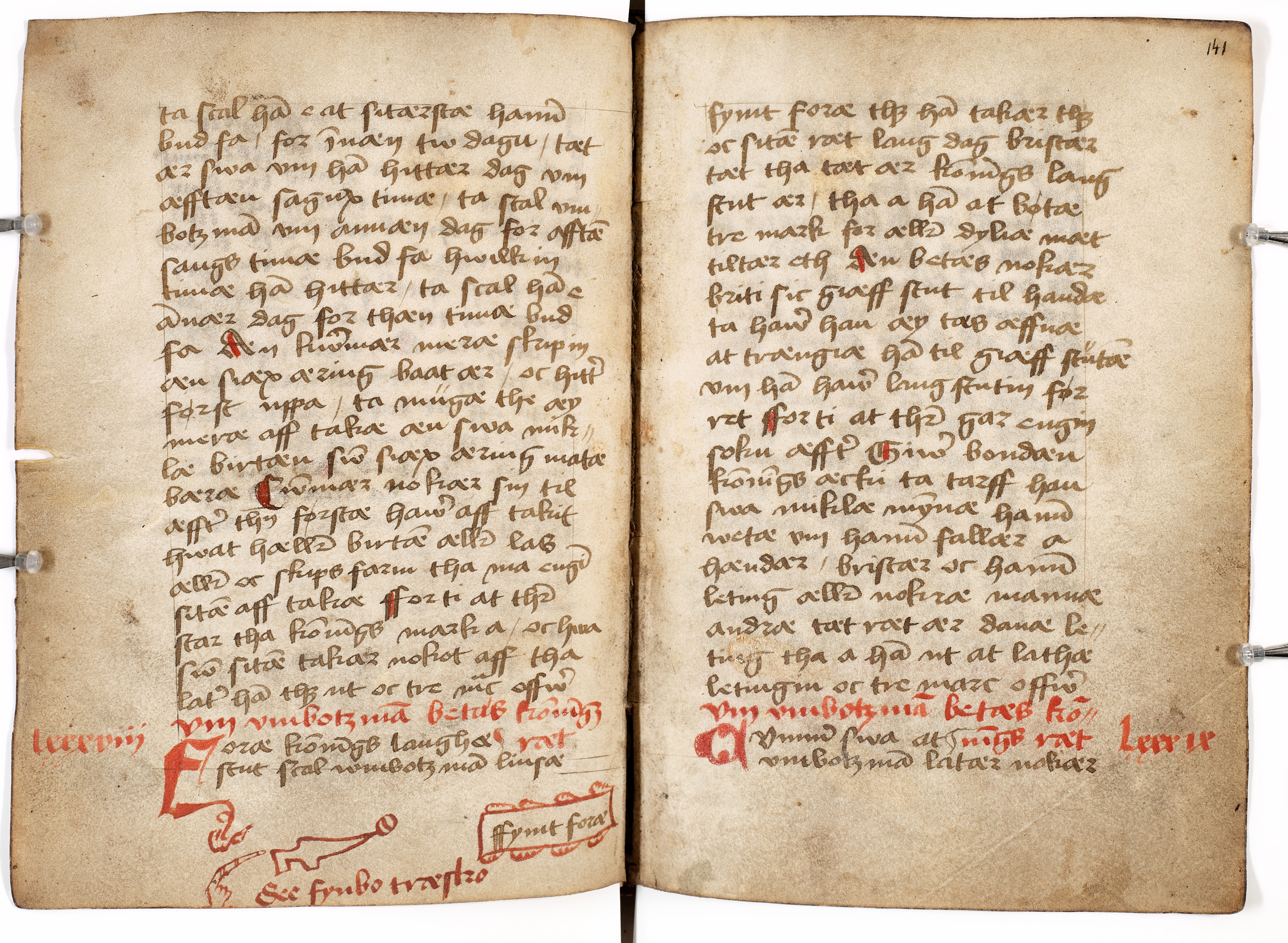

At first glance, the manuscript AM 23 8vo appears to fit the mould of other late medieval Danish lawbooks. Its collection of Zealandic and Jutlandic law codes is written in a single hand using a hybrid script, with red rubrics and enlarged red initials marking new sections of the text. Like many Danish legal manuscripts from the late fifteenth century, the date, place and scribe of AM 23 8vo are also known: the scribe identifies himself as Laurentius Petri, rector of the school in Skælskør on the western coast of Zealand, and dates the completion of his manuscript to the year 1481.

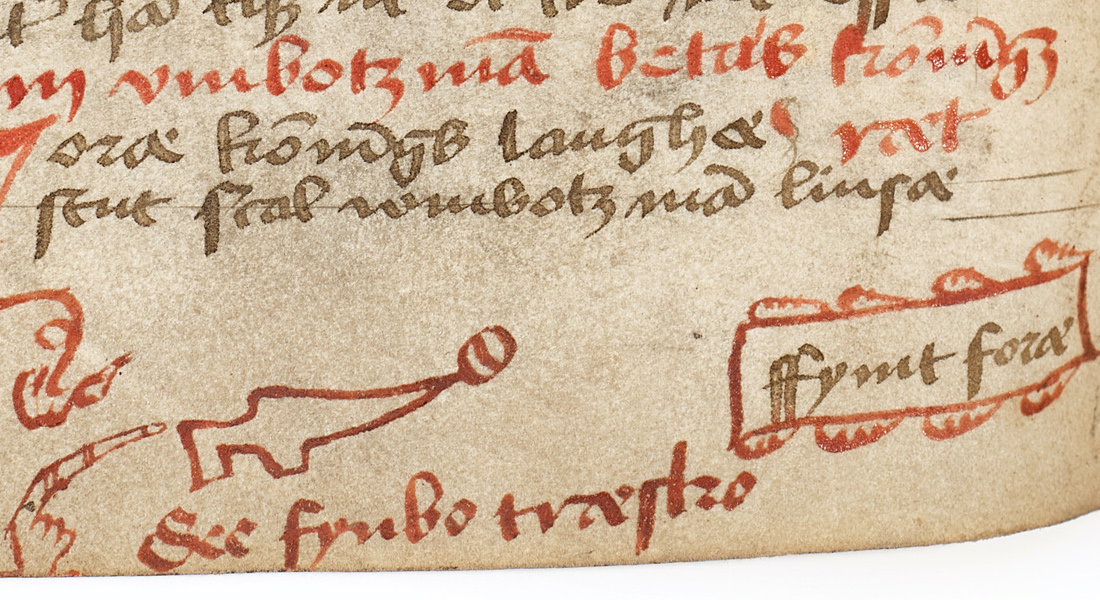

One of the more curious features of the school rector's manuscript, however, is a drawing in the bottom margin on f. 140v, in which a manicula points to a clog and proclaims "See fynbo træsko" ("Behold a Funen clog").

One might cast this curious feature aside as one of the many inexplicable marginal drawings found in medieval manuscripts, but Danish philologist Britta Olrik Frederiksen believes there is more at play here than mere mockery of Funen residents and their footwear.

In her article "Fynsk træsko i Sjællandsk lov" ("Funen clog in Zealand law"), Frederiksen examines the Funen clog and two other drawings found in the bottom margins of AM 23 8vo. Far from being random doodles of a bored scribe, argues Frederiksen, all three drawings relate directly to the text and show the wittier side of the Skælskør schoolmaster.

The Funen Clog

The drawing found at the bottom margin of f. 140v clearly represents a wooden clog made from a single hollowed-out piece of wood, the perfect piece of footwear in a wet and cold agricultural climate such as Denmark. This type of clog grew in popularity among the European peasantry in the fifteenth century, spreading from France northwards.

Types of footwear have frequently represented the oppressed peasantry and the multiple uprisings that took place during the Medieval period. For example, a series of peasant rebellions in Germany around the turn of the sixteenth century known as the Bundshuh-Bewegung ('Bundshuh-movement') takes its name from the footwear used by the peasants at the time. In France, a wooden shoe worn by peasants was known as a sabot, and to trample something with a wooden shoe was described with the verb saboter, which gave rise to the word sabotage.

Does the Funen clog also represent an uprising in the peasantry? Fifteenth-century Denmark saw a series of peasant revolts and a period of economic and social restructuring, partly due to an agricultural crisis which took place from ca. 1350-1450. A nationwide revolt which took place from 1438-1441 would have been recent history when Laurentius Petri doodled the shoe in 1481, while more localized revolts would have been even more recent, such as one that took place in Slesvig in 1472.

Considering this symbolism for the peasantry, Frederiksen argues the placement of the Funen clog at the bottom of f. 140v to be no coincidence. It is placed right at the beginning of Book 3, Chapter 63 of King Erik's law code for Zealand (Eriks sjællandske Lov) among a series of chapters dealing with the various rights of the king. The chapter's rubric "vm vmbotzman betæs konnings ræt" ("If the official asks for the king's due") is misplaced, belonging instead to the following chapter; the correct rubric would have been "Um konnings laghstuth" ("On the king's lawful tax") ― that is, tax owed to the king, which was typically paid in grain. The Funen clog may thus represent the fifteenth-century peasantry recovering from an agricultural crisis and revolting over an oppressive taxation.

The Chaste Bouquet

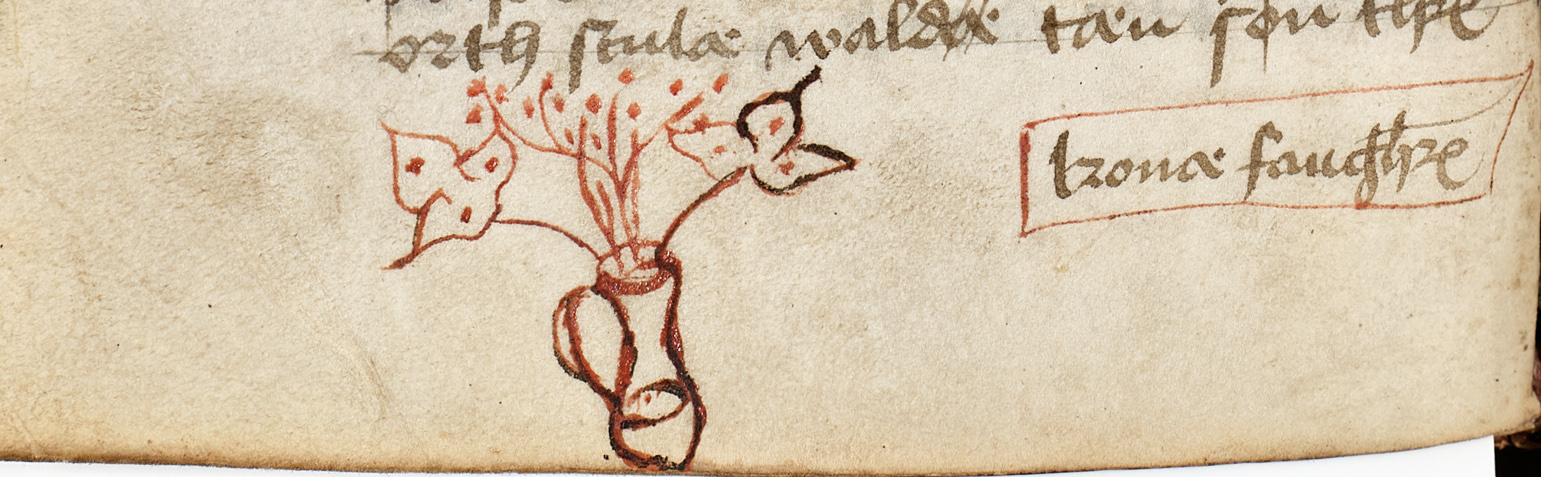

Two further drawings are found in the bottom margins of AM 23 8vo, both of which, Frederiksen argues, are deliberately placed in connection to the text. The bottom of f. 184v shows a vase filled with a bouquet of three flowers resembling French lilies (irises) or fleurs-de-lis, a common symbol of chastity. Similar motifs can be found in the chalk paintings of Danish churches, such as the church in Hyllested.

The text surrounding the vase of lilies is Book 2 of the Law of Jutland (Jyske Lov), which describes the institution of the sandemænd (literally 'truth-men') who acted as witnesses on behalf of the king. Specifically, the page containing the drawing concerns infidelity and who may take legal action against the violation of a concubine's daughter. The symbolism of chastity appears to be a commentary on the text.

A Randy Monk

Things take a turn from the euphemistic to the downright saucy in the third drawing, found at the bottom of f. 234v. The image is placed immediately following the colophon after Valdemar's law for Zealand (Valdemars sjællandske Lov):

Finitus est liber iste jn skelskør In profesto marie magdalene Anno domini Mcdlxxx primo et cetera

"This book was completed in Skælskør the day before Mary Magdalene's day (22 July) in the year of our Lord 1481 et cetera."

Here it is important to recall the Biblical character of Mary Magdalene, who was often identified with the sinful woman in the Gospel of Luke, chapter 7, who washed Jesus' feet, dried them with her hair and poured perfume from an alabaster jar.

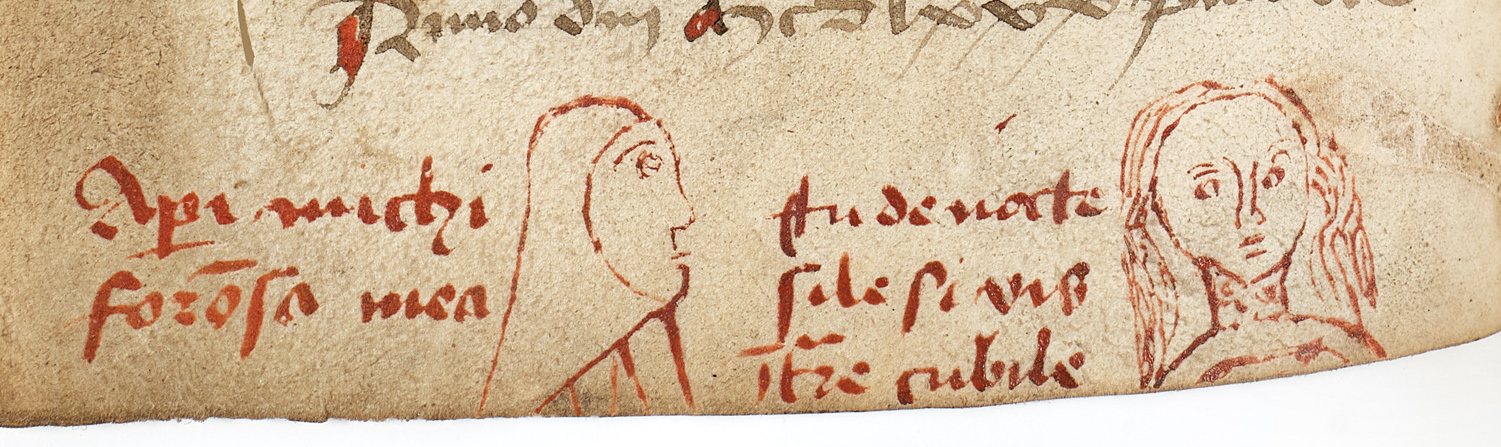

The drawing following the colophon is a little scene with two characters. The one on the left is a man with some type of head covering, likely indicating he is a monk. On the right is a woman with her hair let down.

Next to each character is a short piece of dialogue, in Latin. The monk appears to say to the woman "Aperi michi formosa mea" ("Open up for me, my beautiful!"), to which the woman responds "Tu de nocte sile si vis intrare cubile" ("You must be silent before dawn if you want to enter the chamber"). From the sounds of it, the monk was trying to employ the services of the woman.

The monk's words strongly resemble those found in Song of Songs 5:2, which in the Vulgate reads "Aperi mihi, soror mea, amica mea" ("Open up for me, my sister, my friend"). Meanwhile, the woman's response is reminiscent of chapters 3 and 8 of the same Old Testament book, which were to be read on Mary Magdalene's day following the liturgical calendar. This marginal drawing, however indiscrete, may quite simply be a commentary on the dating of the manuscript!

What at first seem innocent (or perhaps not so innocent) drawings in AM 23 8vo turn out to be witty commentaries on the surrounding text. Clearly Laurentius Petri was not only a trained scribe and schoolmaster; he was also an artist with a clever sense of humour.

Contact

Seán Vrieland is a postdoc at the Arnamagnæan Collection.

Telephone: +45 3533 7566

sean.vrieland@hum.ku.dk

Acknowledgements

This instalment of Manuscript of the Month is based on the article "Fynsk træsko

Read the original article (in Danish) at http://kismet.press/portfolio/from-text-to-artefact/.

Contribute to Manuscript of the Month

Have something to say about one or more manuscripts in the Arnamagnæn Collection? Contribute to the column Manuscript of the Month to get your research out there! Write to Seán Vrieland (sean.vrieland@hum.ku.dk) for more details.