A Scribe’s Favourite Exemplum?

AM 578 i 4to is an Icelandic paper manuscript, which among other things contains a copy of the story of Sníðúlfur and his unfaithful wife that the scribe Magnús Ketilsson has copied several times.

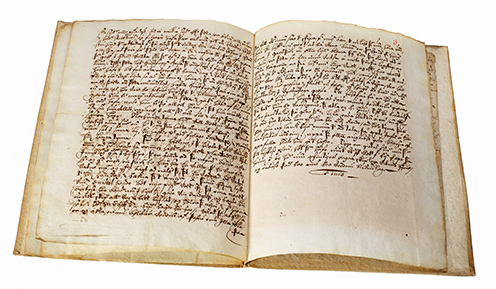

AM 578 i 4to is a fragmentary Icelandic paper manuscript consisting of two parts that originally belonged to separate manuscripts. The first part contains an exemplum — a short tale that could be used in aid of preaching — about a man called Sníðúlfur (fols 1–3), while the second part contains three other exempla: one about three monks, one about a farmer and a bird, and one about two young merchants (fols 4–5). It is the story of Sníðúlfur, and the scribe who copied it, that this article focuses on.

The Scribe

As it survives today, the beginning of the story on fol. 1r was added by a scribe working after the remainder of the text, on fols 2r–3r, was copied; this is reinforced by the fact that the front flyleaf and fol. 1 are clearly of a different, sturdier paper than the older, thinner paper of fols 2–3. Moreover, fol. 1v is blank. In his catalogue, Kålund dated AM 578 i 4to broadly, to the second half of the 17th century, but the date of at least the original copy of the first text (that is, fols 2r–3r) can be narrowed down by considering its scribe, whose cursive hand has been identified as that of Magnús Ketilsson (c. 1675–1709). Based on this, we can date the copy to the last few years of the seventeenth century, most probably between 1696 and 1699.

Magnús Ketilsson was one of the last scribes to work for the wealthy landowner and patron of manuscripts Magnús Jónsson í Vigur (1637–1702), and he was involved in copying several texts for him in about a dozen manuscripts. After his father Ketill Eiriksson’s death around 1690, Magnús Ketilsson also became the foster son of Magnús Jónsson, who ensured that he received a good education. Magnús Ketilsson attended the Latin school at Skálholt, and in 1696 he graduated and returned to his foster father’s household on the island of Vigur in the Westfjords. It was then that he worked as a scribe for only a few years before leaving for eastern Iceland in 1700 to take up a position as a minister of the Lutheran Church.

The Story of Sníðúlfur

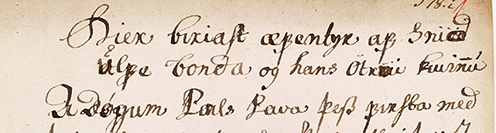

But what of the story he copied in AM 578 i 4to? It tells of a farmer and his unfaithful wife, (“…af Snïdulfe bonda og hans ötru kuinnu”, fol. 1r) and has its roots several centuries earlier, in a medieval Latin life of St Gangulphus of Burgundy, said to be martyred by his wife’s lover in the year 760, and whose feast day is still celebrated in some areas of Europe on 11 May. How exactly the story of an obscure Merovingian saint eventually came to be known and used in Iceland requires further focused research, but it first appears in medieval Iceland as an exemplum. The late 14th-century manuscript AM 657 a 4to includes a copy of it where the eponymous character has the Latinate name Sindulfus. When it is copied over 300 years later in the Westfjords of Iceland, the name looks a bit different (and a bit more Icelandic) as Snidulfur, or in normalized Icelandic, Sníðúlfur. However it made its way to Iceland, the story seems to have been appreciated there, and perhaps especially at the end of the 17th century.

Repeated copies

Magnús Ketillson, the scribe responsible for the copy in AM 578 i 4to, wrote out the same story at least twice more, into books we know were made for his patron and foster father Magnús Jónsson í Vigur. Both of these other manuscripts are now housed in the British Library — a particularly fine copy in Add. 4859 fol. and another in Add. 11,153 4to. Interestingly enough, the latter already contained a shorter copy of the Sníðúlfur story (transcribed by another scribe, Jón Þórðarson), before Magnús Ketilsson added his to the end of that book. It begs the question, whether the story of Sníðúlfur could have been a particular favourite of his. Perhaps he recognised its potential as a preaching aid and went on to use it himself in his short-lived career as a minister. Or perhaps he appreciated it, along with so many other similar texts that could be found in his patron’s collection of medieval and contemporary literature, purely for entertainment’s sake.

Contact

Sheryl McDonald Werronen is a Marie Skłodowska-Curie postdoc fellow (Horizon 2020) at the Arnamagnæan Institute.

Bibliography:

Loth, Agnete. Om håndskrifter fra Vigur I Magnús Jónssons tid. Tre bidrag”, Opuscula III, Bibliotheca Arnamagnæana, Vol. XXIX, København: Munksgaard/Den Arnamagnæanske Kommission, 1967, s. 92-100.