A Prayer Book for the Entire Year — And Every Occasion

December means another year is coming to a close, at least according to our modern secular calendar. The liturgical year, on the other hand, has just begun with the first Sunday of Advent. A sixteenth-century prayer book from Funen contains a series of prayers in Danish to be read during the course of the entire year, as well as on specific occasions like travel or illness.

During the period leading up to the Reformation, which officially took foothold in Denmark in 1536, pious Christians used handwritten books brimming with prayers to Christ, Virgin Mary, and hundreds of saints to practice their religious devotion at home, on the road, or in a monastic environment. AM 784 4to in the Arnamagnæan Collection is one of these Catholic prayer books that contain a variety of prayers in a mixture of Latin and the local vernacular language — in this case, Danish.

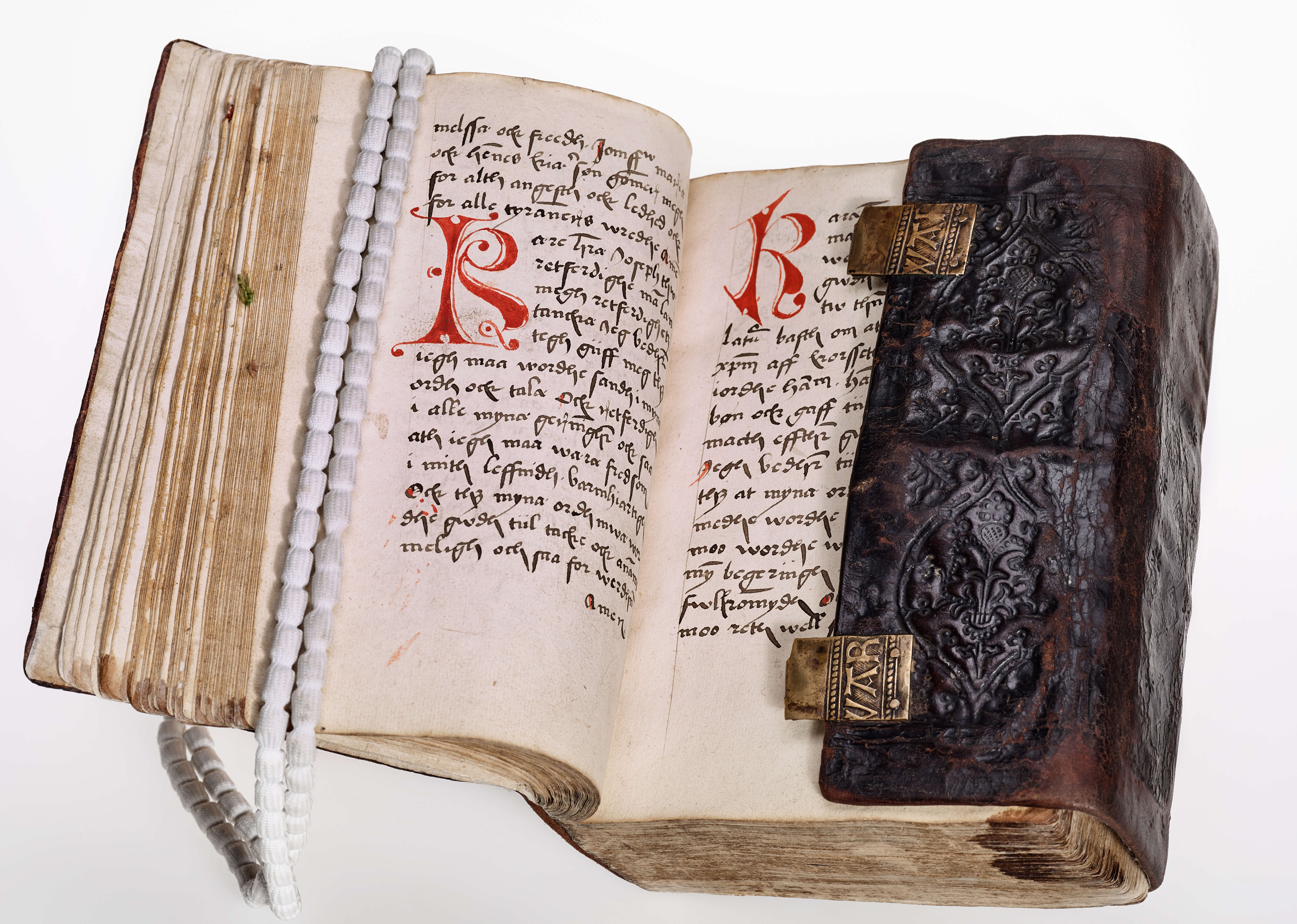

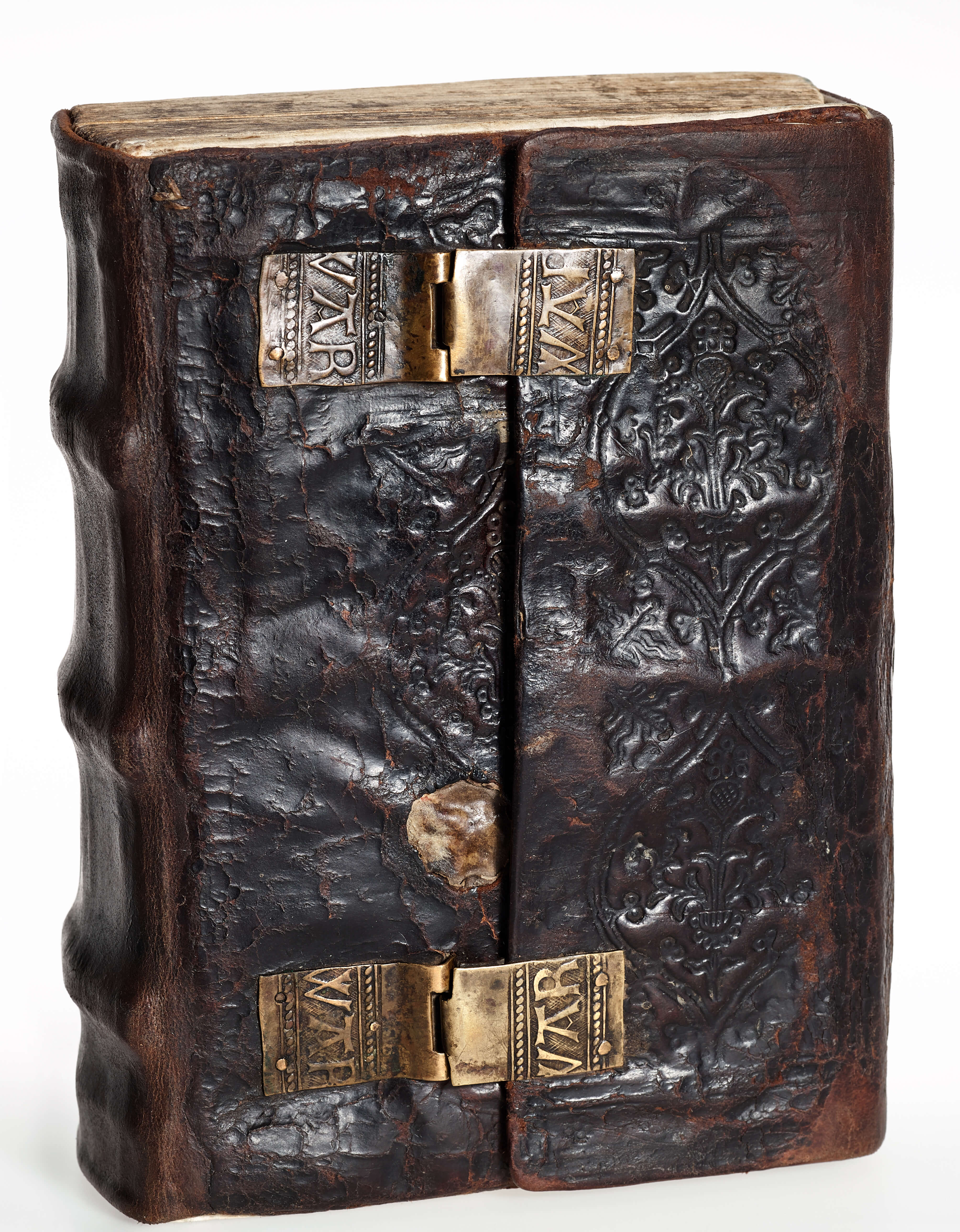

With its paper leaves measuring 192 x 180 mm, AM 784 4to is roughly the size of a paperback novel. An original sixteenth-century leather binding with brass clasps, which are still preserved, made it easy for the book to be carried around. Inside the binding, AM 784 4to contains hundreds of prayers, mostly in Danish, written by multiple scribes.

Many prayers found in prayer books are rather common and are known from multiple manuscripts and in multiple languages. One such popular text in AM 784 4to is a series of fifteen short prayers to Christ, each beginning with the exclamation “O!”, and is therefore sometimes referred to as The Fifteen Os (ff. 5r-7r). This set of prayers is sometimes attributed to St. Bridget of Sweden and is known in translations to other languages as well.

Not all texts in prayer books are literal prayers. Among promises of repentance and petitions for good health and salvation, the reader can find instructions on how to practice their religious devotion. Often these instructional texts are written in red, resembling a rubric that assists in finding a correct prayer or other text to be read for nearly any conceivable occasion.

Take the winter season, for example. Many of us might be feeling a bit under the weather during these cold months. An instructional text in AM 784 4to informs the user which masses should be read for such a malady, including the masses of the physician Saints Cosmas and Damian, Saint King Sigismund, and holy virgins Agatha and Apollonia (f. 4r).

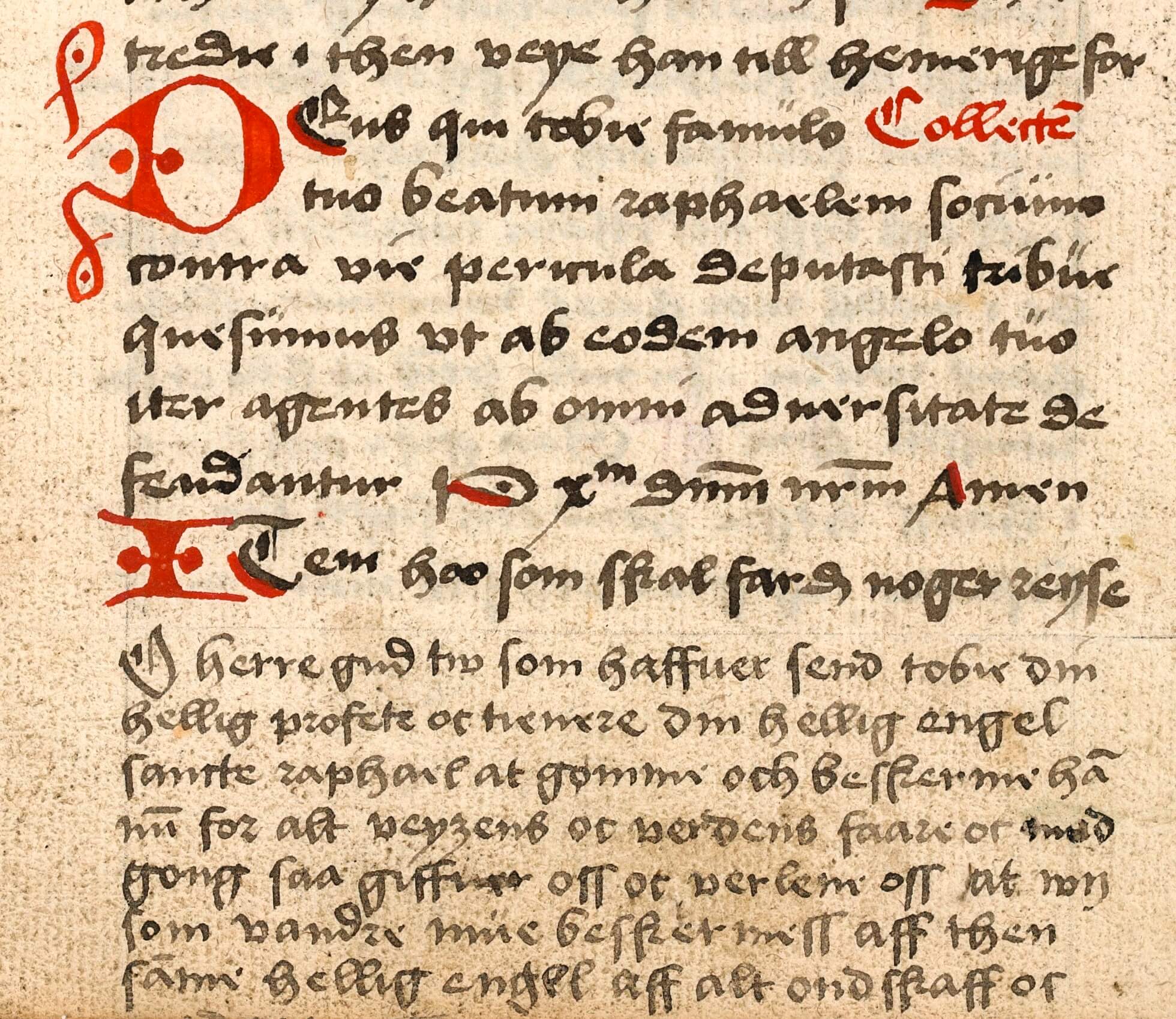

This season can also involve a lot of travel. Here again, AM 784 4to provides us with handy advice. One prayer opens with an instructional text in red, which reads: “When your friend departs from you, make two signs of the cross between his shoulders and one on his breast and read the following three times, etc.” (f. 26r). The following prayer is also intended for a travelling friend and opens with the instructions (this time in black): “Likewise when your brother or friend departs from you to anywhere then you shall bless him thus.” What follows is a prayer in Danish, which is introduced with a red enlarged initial. The final part of the prayer, known as the collect, is given in Latin. At the bottom of the page, someone has translated this Latin collect into Danish (f. 26v).

Prayers for the whole year

A large portion of the manuscript, covering more than 250 leaves or 500 pages (ff. 80r-338r), contains prayers for the entire calendar year. Rather than our common secular calendar, which begins on 1 January, this section of prayers follows the liturgical or church calendar, which begins on the first Sunday of Advent and continues with saints’ feast days and other Christian holidays until the feast day of St Andrew (30 November).

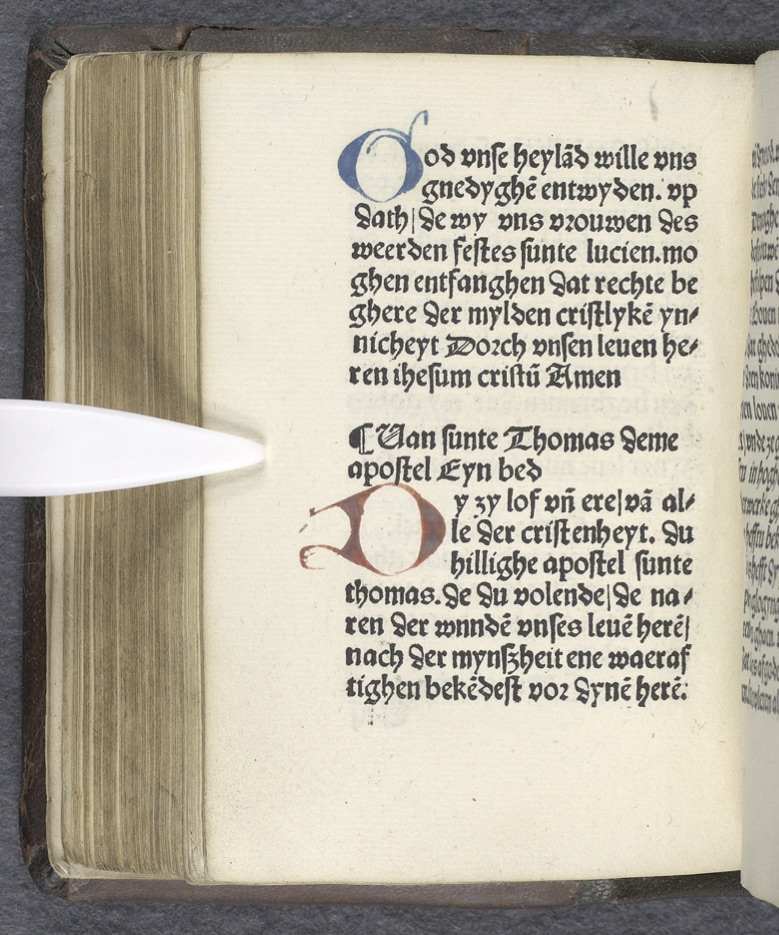

If you are reading this Manuscript of the Month at the time of its publication (15 December), then it is right between the feasts of St. Lucia (13 December) and St. Thomas the Apostle (21 December), prayers to whom are found one after the other in AM 784 4to. The following pages — nearly thirty leaves of the manuscript (ff. 97v-126r) — are dedicated to the season’s main events: Christmas Eve (24 December) and Christmas Day (25 December).

While it seems convenient to combine prayers for both movable and immovable liturgical feasts for the entire year in a single book, this practice was not widespread. Many late medieval prayer books focus only on a selected assemblage of saints and feasts favorable for the intended user or commissioner. In this respect, AM 784 4to is quite unique among its type, so it is no surprise that one of its scribes refers to this collection as Eth Spægell fwld aff ald Wisshed (“A mirror filled with all wisdom”) in a colophon at the end of this series of prayers (f. 338r-v). Because of this colophon, the text has since been given the name Visdoms Spejl (“Mirror of Wisdom”) in Danish literary research.

Visdoms Spejl is, however, also found in a second Arnamagnæan manuscript, AM 782 4to, although the texts differ slightly in the two manuscripts. For example, both manuscripts have a prayer to St. Anne, the mother of the Virgin Mary according to later traditions, to be said on her feast day on 9 December. However, while in AM 782 4to this prayer is followed by a series of nine prayers to St. Anne, in AM 784 4to it is followed by a prayer to both the Virgin Mary and St. Anne, the beginning of which opens with lines from the well-known Ave Maria.

Despite this and other differences, Karl Martin Nielsen (1945: I, xxxv) believed the two manuscripts to be copies of the same examplar. This exemplar is now lost and the ultimate source of Visdoms Spejl is not known.

Judging solely by its name, Visdoms Spejl shapes itself as a part of a popular literary genre of a “Mirror” (known in Latin as “Speculum”). A speculum as usually defined as a type of encyclopedia, often in the form of a dialogue. Well-known examples include Vincent de Beauvais’ Speculum Historiale (“Mirror of History”) and the Norwegian Konungs Skuggsjá (“King’s Mirror”). However, in late medieval devotional literature, a “mirror”can designate a collection of devotional instructions and catechismal explanations in a vernacular meant predominantly for laypeople — and Visdoms Spejl follows this trend.

Lay devotional mirrors were not only spread in manuscripts but also as incunabula (early printed books). And it is not a coincidence that the text closest to Visdoms Spejl is a book printed by the Lübeck printer Steffen Arndes in 1487 under the title De Speghel der Sammiticheyt (“The Mirror of Conscience”). At the turn of the sixteenth century, Lübeck was a vibrnat center of printing religious literature in the local language, Low German, and these incunabula often found its way into Scandinavian countries.

De Speghel der Sammiticheyt follows the same concept of arranging an extensive amount of prayers according to a liturgical calendar, and about a half of its prayers could have been the source behind the respective Danish prayers in Visdoms Spejl. For example, the prayers to St. Lucia and St. Thomas the Apostle, which follow each other in the printed book, look strikingly similar to the same prayers in AM 784 4to.

Most of the prayers in De Speghel der Sammiticheyt, similarly to Visdoms Spejl, are “hagiographic” in their nature. They often verbosely recount details from a saint’s worldly life starting with familial descent. We only know of one Middle Low German manuscript written in the last decades of the fifteenth century (now in Lübeck) that could stand as a model for the printed text. It is likely that Visdoms Spejl was translated from a similar Middle Low German version of the text which has not yet been identified.

A book for years to come

In the same colophon in AM 784 4to that names the text, the scribe refers to himself as Johannes Johannessen, hypodadasculus (“underteacher”) in Fåborg on southern Funen. The date of writing is given as 1523, the same year that the Danish king Christian II, a protestant, was deposed and exiled to the Netherlands. His uncle ascended the Danish throne as Frederik I and would be the last catholic ruler in Denmark.

As it is a catholic prayer book produced on the cusp of the Reformation, one might expect AM 784 4to did not have many years of use. One of the scribes involved in producing the manuscript, however, thought otherwise.

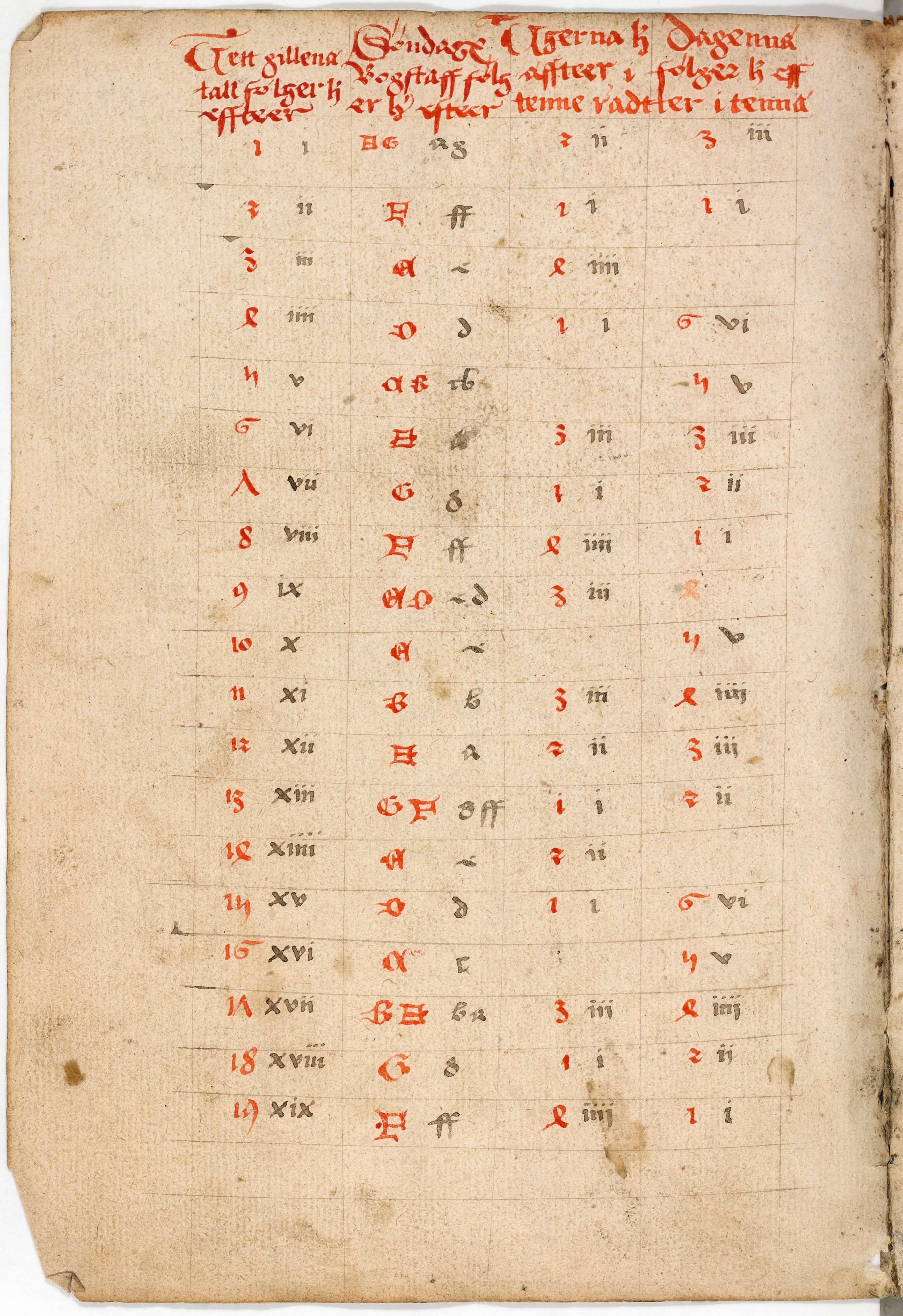

An added leaf near the end of the manuscript contains a type of chart known as an Easter table, a sort of cheat-sheet for calculating the date of Easter. This moveable feast celebrating the most significant event for Christianity follows the lunar calendar, taking place on the first Sunday following the first full moon on or after the vernal equinox (21 March).

The Easter table in AM 784 4to is divided into four columns. The first column gives the so-called Golden Number, a calculation that divides the pascal full moon into a nineteen-year cycle. One can see the numbers 1-19 given in both roman and arabic numerals.

The second column gives the so-called Dominical Letter or Sunday Letter, a way of re-using calendars year after year by assigning letters to the days of the week. From the first line of the chart we can see the first year was a leap year which began on a Sunday, explaining the two dominical letters A and G.

The third and fourth columns show the number of weeks and days from Candlemas (2 February) until Quinquagesima Sunday, the final Sunday before the Lenten fasting season. (The manuscript also contians a prayer to be read on Quintagesima Sunday, also known as Flæskesøndag or “Pork Sunday”, as pork was traditionally eaten in preparation for the upcoming fast.) On the first line of the Easter table we can see that Quinquagesima Sunday came two weeks and three days after Candlemas; that is, 19 February.

With these columns put together, we can determine the first year mentioned in the Easter table must refer to 1520, a leap year which began on a Sunday and which had a Golden Number of 1. (Easter fell on 8 April that year, meaning Quinquagesima was on 19 February.) The chart then carries on for a full nineteen-year cycle, meaning it could be used until the year 1538, two years following the official introduction of the Reformation into Denmark. Whether AM 784 4to was still used at the time is, however, a different question.

Topics

Contact

Seán D. Vrieland is associate professor at the University of Copenhagen.

Iliana Kandzha is post-doc at the University of Copenhagen.

Bibliography

Chesnutt, Michael. 2003. The Medieval Danish Liturgy of St. Knud Lavard. Opuscula XI:1-159.

Nielsen, Karl Martin. 1946-1982. Middelalderens danske Bønnebøger. København: Det danske Sprog- og Litteraturselskab.

Funding

This entry of Manuscript of the Month was produced in connection with the research project When Danes Prayed in German funded by the Danish Research Council (grant number 1055-00040B).

Contribute to Manuscript of the Month

Have something to say about one or more manuscripts in the Arnamagnæn Collection? Contribute to the column Manuscript of the Month to get your research out there! Write to Seán Vrieland (sean.vrieland@hum.ku.dk) for more details.