Manuscript, Print and the Regional Languages of Early Modern Europe

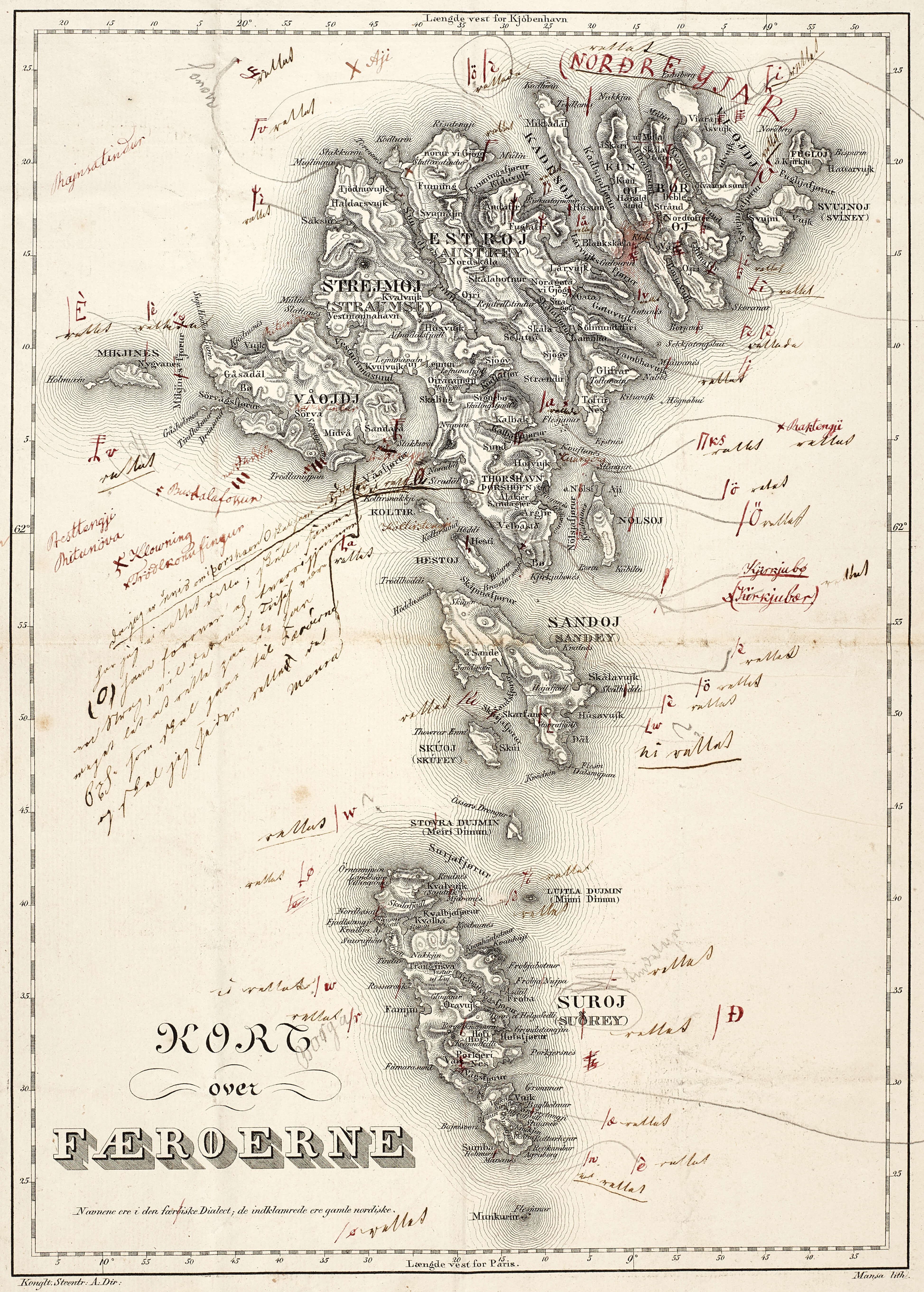

In 1822 the Danish botanist H. C. Lyngbye published an edition of the ballad cycle of Sigurd the Dragon-Slayer, the first printed book using the Faroese language. Intended as much for a Danish audience as a Faroese one, Lyngbye’s edition sparked an interest in the language and oral literature of the Faroe Islands among scholarly circles in Denmark during a period of rising national identity across Europe.

A conference marking the anniversary of this publication explores the manuscript and print cultures of Faroese and other regional vernaculars in Early Modern Europe, ca. 1550-1850. What were the contexts in which smaller languages, some of which had never been written before, were put to paper in the wake of the Enlightenment and the rise of Romanticism? What was the interplay between regional languages and the dominant, national languages in a written context? How did rising levels literacy and access to printing contribute to the production of written texts in Europe’s minority vernaculars?

Thursday, 19 May

9:30 Welcome

Session 1 (10:00-11:30) Printing History

This paper analyses the circumstances of how and why the Norwegian national law of 1274 was revised and brought to print for the first time in 1604 in Copenhagen, titled Den Norske Low-Bog, offuerseet, corrigerit oc forbedrit Anno M.DC.IIII. The basis for this printed edition was the Landslǫg, a national law that had been in force in Norway since 1274. The Landslǫg was written in Old Norwegian, but in the fifteenth century, many Danish translations of this law sprung up. A number of official orders were sent to Norway from the court in Denmark through the latter half of the fifteenth century and the early sixteenth century that attempted to mandate a new, state-sponsored revision of the lawbook in Danish. These were largely ignored. This paper argues that the motivation behind the orders for a state-sponsored revision of the lawbook were to prevent the fragmentation of the Norwegian legal system due to the different versions of the law in circulation, to ensure that the Danish was of high quality in the eventual, authorised translation, and to consolidate Denmark’s political power over Norway. In doing so, the development of the letters to officials and lawmen in Norway is traced from 1557 to 1602, and the eventual preparation and printing of the lawbook of 1604 is also discussed.

Series dynastarum et regum Daniæ (Succession of rulers and kings of Denmark) is a treatise on the oldest Danish royal genealogies written by Þormóður Torfason (1636–1719), an Icelander employed as a royal antiquarian and historiographer at the court of Dano-Norwegian monarchs. After his fruitful but short career as the royal translator of Old Norse-Icelandic sagas in the service of Frederik III (r. 1648–1670), Torfæus was given the assignment of compiling an account of Danish royal genealogies based on Old Norse-Icelandic sources. He completed this assignment in 1664, when he presented the king with a beautiful volume in quarto containing his Series dynastarum (today the manuscript GKS 2449 4to held at the Royal Danish Library in Copenhagen). This work, however, did not appear in print for almost forty years, as the first printed edition appeared in Copenhagen in 1702. This presentation focusses on the production and transmission history of Series dynastarum between manuscript and print medium.

Session 2 (13:00-14:30) Languages in Contact

In this talk I intend to concentrate on the use of English, EN, on the Faroe Islands, and the influence EN has on Faroese, FA. In the first part of the talk focus will be on casual language contact, where it will be shown how speakers handled lexical borrowings, as when EN kelly’s eye (part of a trawl) became kameleyga ‘camel-eye’ in FA. Then I proceed to the present situation, where EN has become the preferred L2 of many younger speakers, partly replacing Danish, DA, and I will give examples of convergence and code-switching between EN and FA in the speech by young speakers. The data is based on recordings among young informants (15-16 yrs. and 10-11 yrs. old), and one recording where a young female informant, a student at Glasir (the High School in Tórshavn) recorded all her speech interaction for 5 hours and 45 minutes.

The talk will thus show what happens in bilingual speech, when speakers move from being passive bilingual to active bilinguals.

Further I will address the question of a possible language shift, based on a match guise test, and a recent study of attitudes towards English, Danish and Faroese.

Scholarship in Norse loanwords in the Gaelic languages implicitly takes the word importers, the settlers and traders in the Hebrides, Scotland, the Isle of Man and Ireland, i.e. the Norse speakers, as being people who came from the more obvious geographies of Iceland or Norway. Although much can be inferred from the linguistic evidence, who the actual people were, their identities and their places of origin can never be known. Moreover, loanword etymologies typically operate with Old Norse/Old Icelandic as the implicit index against which everything is measured: scholarship naturally looks first to Old Norse/Old Icelandic for source words, embracing an array of assumptions about both geography and time period. Of course, the Old Norse/Old Icelandic corpus is large, and assuming this as the source language makes a lot of sense. However, generalizations mask subtle variance. There are certainly loanwords in the Gaelic languages for which there are no recorded Old Norse/Old Icelandic source, while comparable source words can be found in the smaller regional Nordic vernaculars of the North Atlantic.

Using a range of C19th and C20th lexicons in the Gaelic and Nordic languages, this paper discusses, with examples, a small number of loanwords in the Gaelic languages that are attested in the smaller regional Nordic languages other than Old Norse, considers implications of using them as possible proxies for unattested Old Norse/Old Icelandic forms, and discusses the scope for a more nuanced understanding of medieval and early modern linguistic and social conditions in the North Atlantic.

Session 3 (15:00-16:30) Irish and Gaelic Manuscripts

In 1819, Donnchadh Bán Ó Floinn, or Denis O’Flynn, set up a small printing press in his house in County Cork. In his letters to his friend, the antiquarian James Hardiman, he wrote that he was inspired to do so ‘to rekindle in the breasts of my dormant countrymen, once more, that spark of affection which formerly over[awe]’d with the movement of every true Irish writer’s pen, in support of Ireland’s merited fame.’ Hardiman also referred to Ó Floinn’s endeavours, as he did his own, as being ‘for the patriotic purpose’. This paper explores the notion of patriotic printing in the first half of the nineteenth century in Ireland and will examine how, for some antiquarians, the act of printing materials in the Irish language was seen as restoring pride in ‘her ancient language’. At a time when the shift to English was dramatically increasing, it was prophesied by many antiquarians that the printed materials would be the only monument to Irish remaining after the language had ceased to be spoken, as can be seen in John O’Daly’s remark that Irish was ‘a language without a mouth.’ This paper will also investigate how printed copies of the contents of medieval Irish manuscripts served as both a warning of the fate of the modern language and as a catalyst to spark change.

Friday, 20 May

9:30 Welcome

Session 4 (10:00–11:30) Performance and Identity

Language is more than merely a means of communication; it is also a primary marker of collective identity, through which notions of selfhood are (re)negotiated and confirmed on a daily basis. This dynamic aspect of language may not always be at the forefront of our minds, but in nineteenth-century Europe, it was especially this ethnogenic quality of language that captivated the imagination of zealous intellectuals and romantic nationalists. In this paper, I will argue that the urge to standardize the mother tongue and “purge” it from foreign influences was felt most strongly in small and “peripheral” nations, where the acute threat posed by the linguistic hegemony of a dominant “foreign” ruling class was perceived as an existential one. As the comparison of the Frisian and Faroese case studies will demonstrate, this linguistic activism dovetailed with a growing interest in (Old Norse-Icelandic and Frisian) medieval manuscripts, perceived as vestiges of undiluted linguistic authenticity, coinciding with a more general infatuation with Nordic culture and all things “runic”. How were these ancient sources mobilized to inspire a cultural and linguistic rejuvenation in the present? By applying the biological concepts of ‘character displacement’ and ‘reverse cline’ to the analysis of philological debates and polemics concerning the purification, standardization, and orthography of the Frisian and Faroese language, I will demonstrate how the cultural performance of ‘northernness’ (vis-à-vis the southern hegemons of Holland and Denmark, respectively) has left its mark on the cultural and linguistic development of these small nations.

Chain dancing was listed on the UNESCO inventory of “intangible cultural heritage” of the Faroe Islands in 2020 - but the actual implications are not clear. Speaking of a particular cultural practice as common property - “heritage” of the wider Faroese community inevitably affects the way the practise is presented and perceived in various ways and eventually changes the way people relate to it. Questions on authenticity and ownership arise and some tensions may occur - both among those “carrying the culture” and among those expected to claim or at least value the practise as part of their heritage. In this paper I will be going through the background of the current understanding of the Chain dance as “national culture” and discuss how this label affects contemporary dance. The paper is based on ethnological field work, mainly participant observations, and interviews during 2017-2020. However, I will also be referring to early writings on the Faroese Chain Dance in order to explore how a dance once despised and ridiculed by the general public ended up as a national treasure and eventually an obligation.

Session 5 (13:00–14:30) Sjúrðar kvæði — 200 Years of Faroese in Print

H. C. Lyngbye's Færøiske Qvæder om Sigurd Fofnersbane og hans Æt (1822) is highly regarded as the first book printed in the Faroese language. Its publication coincided with the birth and blossoming of a new Faroese writing culture, wherein scribes on the Faroe Islands produced manuscripts for scholarly networks in Copenhagen in their pursuit to publish Faroese literature, especially the kvæði. This paper highlights the manuscripts and their makers behind the publication of Lyngbye's Færøiske Qvæder.

Session 6 (15:00–16:30) Manuscripts at Føroya Landsbókasavn